Community-based Strategies for Optimising Mangrove Forest Tourism Management in Balang Baru Village, Jeneponto Regency

Abstract

Although SWOT analysis has been widely used for tourism and conservation planning, its application here highlights the institutional and social dynamics shaping mangrove ecotourism in a rural Indonesian context. The study reframes SWOT not merely as a planning tool but as a policy instrument to show how local collaboration, governance capacity and ecological rehabilitation can be aligned to sustain mangrove-based livelihoods. Grounded in the context of Balang Baru Village, where mangrove resources managed as a tourism area face increasing pressure from population growth and economic needs, this study aims to optimise the utilisation of the mangrove forest tourism area through the formulation of effective management strategies. Primary data were obtained from interviews with 15 respondents, including local residents, village government representatives, and members of the mangrove management group. The results identified ten strategic actions to strengthen mangrove tourism management, including the use of non-tourism zones for rehabilitation, the development of mangrove education parks, the establishment of an official tourism website, the improvement of facilities and infrastructure, and the enhancement of stakeholder collaboration. These strategies are expected to support sustainable mangrove management while improving community welfare through ecotourism development.

1. Introduction

Mangrove forests are known as coastal vegetation, tidal plants, or brackish forest species that grow and develop around coastal areas where the soil is typically sandy, consists of coral reefs, or is alluvial in nature. Mangrove forests are widely distributed along Indonesia’s coastlines and thrive in areas influenced by tidal fluctuations. They represent a unique ecological feature of coastal ecosystems due to their dual characteristics as both terrestrial and marine habitats (Hastuti & Salsabila, 2022).

The physical functions of mangrove forests include regulating the boundary between groundwater and seawater, serving as natural barriers, facilitating land accretion, and protecting the coastline from erosion and abrasion (Mappiasse & Mukhlisa, 2024). Ecologically, mangrove ecosystems provide feeding and breeding grounds for aquatic fauna such as fish, shrimp, crabs and shellfish. They also act as nursery grounds and important habitats for various animal species, either as primary or temporary habitats. Economically, mangrove forests provide resources such as firewood, timber, charcoal, and medicinal plants. Furthermore, they protect coastal areas from wave action, absorb heavy metals from the soil and most importantly play a key role in carbon sequestration, thereby reducing the effects of global warming (Mhatre, 2024).

The management of coastal regions, particularly mangrove forest areas, is therefore essential. Community participation is crucial in this context, by improving the local economy through sustainable management (Sabar et al., 2025). Moreover, from an ecological perspective, mangrove conservation is one key approach to mitigate environmental degradation which can be assessed from community management. From an economic perspective, the development of mangrove-based ecotourism represents a promising alternative given the high potential value of these ecosystems (Putri et al., 2025).

Since 2018, the government of Balang Baru Village has managed its mangrove forest as a tourism area, resulting in reduced forest degradation and improved local economic conditions. Arfiani (2021) compared mangrove forest areas for tourism in Balang Baru village with those combining mangroves and aquaculture ponds in Paccelanga subdistrict, showing that tourism-oriented mangrove areas have a higher economic value than those mixed with aquaculture. Similarly, Kasnir et al. (2021) argued that community-based mangrove management strategies significantly improve local economic conditions. Ely et al. (2021) also emphasised that mangrove degradation can be mitigated through appropriate and sustainable management systems, which require identifying key degradation drivers and designing effective management strategies. Moreover, Adinugroho et al. (2023) mention several threats to mangrove tourism parks, including competition from newly developed tourist destinations, which reduce visitor numbers and weaken site recognition.

Drawing from these findings, this research underscores the importance of optimising mangrove forest tourism management to enhance the potential of mangrove tourism areas. The study aims to develop community-based management strategies for the sustainable use of mangrove forests as tourism services, contributing to a more resilient and ecologically balanced environment. Thus, employing SWOT this research investigates internal and external factors that influence mangrove tourism management in Balang Baru Village and proposes strategic actions that can strengthen ecological protection, improve infrastructure, and reinforce local governance and community collaboration in tourism development.

2. Method

This research was conducted in an area known as Mangrove Idaman at Balang Baru Village, Tarowang, Jeneponto Regency. The study took place from January to March 2025. Data were collected through field surveys and interviews where key respondents were selected using purposive sampling technique. This method allows the deliberate selection of respondents based on their relevance to the research objectives and their direct involvement in mangrove forest management.

A total of 15 respondents participated in the study, comprising ten residents living near the mangrove forest area, two representatives from the Balang Loe Village government and three members of the mangrove tourism management group (the chairperson, secretary and one active member). The interviews covered topics related to the management of the mangrove tourism area, forms of utilisation by surrounding communities, existing institutional arrangements and the roles and collaboration among stakeholders and relevant government agencies.

The research employed a qualitative descriptive approach, supported by visual documentation (photographs) and secondary data obtained from literature, reports and previous studies. Primary data were collected through interviews, while secondary data were sourced from supporting references such as scientific articles, reports, and policy documents.

Following the approach of Mashuri (2020), the SWOT analysis was used to identify internal and external factors affecting mangrove ecosystem management. Internal factors consist of strengths and weaknesses, while external factors include opportunities and threats such as environmental conflicts or social issues that influence management outcomes. SWOT analysis was then used to formulate management strategies by linking these factors systematically.

The logic behind this analysis is to maximise the area’s existing strengths and opportunities while minimising its weaknesses and threats. Through this process, the study identifies strategic directions that can be applied to optimise the sustainable management of the Balang Baru mangrove tourism area

3. Result and Discussion

1) Description of the Mangrove Tourism Management Area

The mangrove forest tourism area in this reaserach is managed collaboratively by the village government and local residents. The total mangrove forest area covers approximately 20 hectares, of which 2 hectares have been designated as a mangrove tourism zone. The Mangrove Idaman site has previously experienced degradation caused by land conversion to aquaculture ponds by surrounding communities. According to Sila (2021), forest degradation resulted from community activities that deliberately converted coastal mangrove zones into fishponds. Most of these ponds, located along the shoreline have suffered structural damage or leakage, thus forcing owners to incur additional costs for repairs.

2) Forms of Utilisation of the Mangrove Ecosystem

This research identified at least two primary forms of mangrove utilisation in Balang Baru Village:

a) Tourism Activities

The Mangrove Idaman site, managed by the Balang Baru Village government, spans 2 hectares and has become one of Jeneponto Regency’s distinctive tourist destinations. The main attraction lies in the panoramic view of the open sea framed by mangrove vegetation. Existing facilities include parking areas, an entrance gate, rest areas, gazebos and photo spots designed to improve visitor comfort and accessibility.

b) Capture Fisheries

Fishing remains a key livelihood for the local community surrounding the mangrove area. Residents commonly catch fish, shrimp and crabs within and beyond the mangrove zone. In addition, several villagers are engaged in seaweed farming. These activities constitute the main source of household income and reinforce the socio-economic dependence of the community on the mangrove ecosystem.

3) Internal Factors in Mangrove Tourism Management

Based on field interviews, the internal factors consist of strengths and weaknesses that directly influence the management of the mangrove tourism area.

Strengths:

a) The mangrove area allocated for tourism covers 2 hectares within a total mangrove forest of 20 hectares (S1).

b) The site has strong potential for further development as an ecotourism destination (S2).

c) The village government and surrounding community actively contribute to management efforts (S3).

Weaknesses:

a) Inadequate tourism facilities and infrastructure (W1).

b) The site visibility and popularity have declined over the years (W2).

c) Limited outreach and socialisation regarding mangrove management practices (W3).

d) Insufficient stakeholder coordination in managing the mangrove tourism area (W4).

4) External Factors in Mangrove Tourism Management

External factors encompass opportunities and threats that arise from the wider environment.

Opportunities:

a) The area is frequently used for mangrove seedling programmes and rehabilitation activities (O1).

b) The site attracts academic research on mangrove and ecotourism themes (O2).

c) The tourism sector receives promotional support from the Jeneponto Regency Tourism Office (O3).

Threats:

a) The site is often Utilise without formal permission (T1).

b) Growing competition from other emerging tourism destinations in Jeneponto (T2).

5) SWOT Analysis Matrix and Strategy Formulation

The SWOT analysis combined internal and external factors to determine strategic options for managing the Mangrove Idaman tourism area. The results are summarised in Table 1, which presents the interaction between strengths (S), weaknesses (W), opportunities (O), and threats (T), and the corresponding strategic responses (SO, WO, ST, WT).

Table 1. SWOT Matrix for Mangrove Idaman Tourism Area Management

6) Interpretation of the Strategies

a) Utilisation of non-tourism zones for rehabilitation (SO)

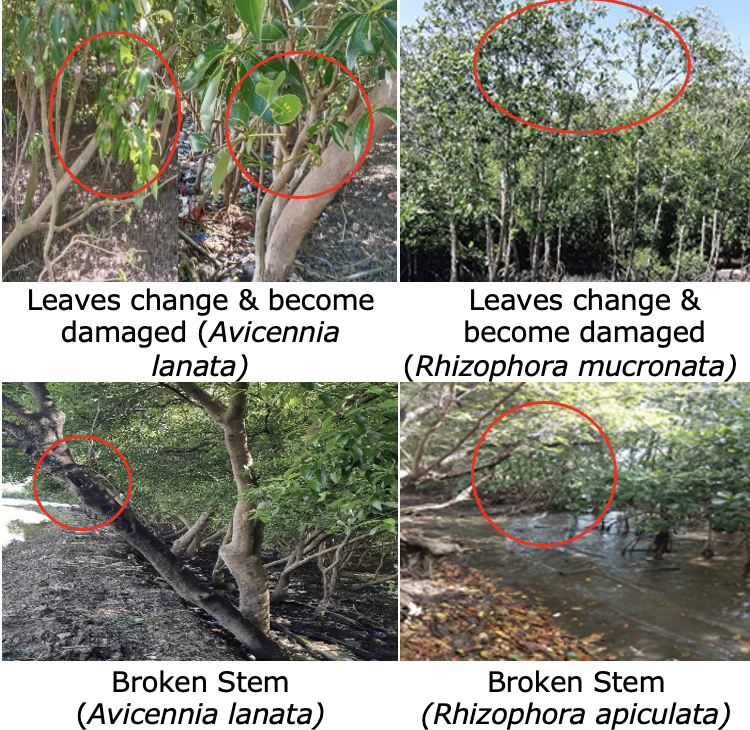

In Balang Baru there are two dominant species—Rhizophora mucronata and Avicennia marina are known for their resilience and rapid growth, making them ideal for planting and rehabilitation activities. Several degraded coastal areas can be restored as natural coastal protection zones. Rehabilitation activities covering approximately 10 hectares were carried out by local communities in collaboration with BPDASHL Jeneberang Saddang under the 2020 National Economic Recovery (PEN) Padat Karya Mangrove Planting Programme (Arfiani et al., 2021b). However, because no post-planting monitoring was conducted, the outcomes were limited. This indicates the need for renewed, community-based rehabilitation beyond the current tourism zone (Meirezaldi et al., 2024).

b) Development of an educational mangrove park (SO)

Beyond recreation, the mangrove tourism area can function as an educational park (taman edukasi) where visitors learn about mangrove ecosystems. This approach aligns with Purwindiyanto et al. (2020) which describe edutourism as a form of tourism that combines learning and recreation. At Mangrove Idaman, such facilities can help visitors and students understand mangrove species, ecosystem functions and carbon sequestration roles, while strengthening conservation awareness and supporting the local economy.

c) Creation of an official tourism website or application (SO)

In the digital era, an official website or mobile application is vital for promoting Mangrove Idaman (Saputra & Suniantara, 2023). This platform can provide comprehensive and reliable information about routes, facilities, biodiversity and rehabilitation activities. Integration with social-media channels such as Instagram, Facebook, Tiktok and Youtube can expand outreach through interactive content, photos, and short videos, thereby increasing visitor interest and strengthening the site’s brand visibility.

d) Improvement of facilities and infrastructure (WO)

To support seedling and rehabilitation activities, the existing facilities and infrastructure must be evaluated and upgraded systematically. This includes repairing damaged walkways, docks, rest areas and water systems, while providing new amenities such as prayer rooms, sanitation facilities, electricity and lodging. Environmentally friendly materials—bamboo or sustainably sourced wood—should be used to minimise ecological impact. These improvements will enhance visitor comfort and operational efficiency in the Mangrove Idaman tourism area.

e) Utilisation of research and publications to enhance visibility (WO)

Research and academic publications play an important role in maintaining the visibility and reputation of the Mangrove Idaman site. Collaborative studies with universities and research institutions can help identify management problems, introduce innovation, and promote the area as a “living laboratory.” Publications arising from such research increase the site’s exposure and attract both researchers and tourists who wish to participate in mangrove rehabilitation or conservation activities.

f) Capacity building and awareness for local managers (WO)

According to population data, most residents living near the mangrove tourism area in Balang Baru have only completed primary education. Consequently, knowledge of sustainable mangrove management remains limited. Regular socialisation and training programmes for the management group and local residents are essential to build understanding of conservation principles, improve skills, and reduce unsustainable practices that could lead to further degradation.

g) Strengthening stakeholder collaboration (WO)

The current management of the Balang Baru mangrove area relies heavily on village funds. Therefore, partnerships with multiple stakeholders are crucial to support long-term sustainability. For example, the 2020 PEN Padat Karya Mangrove Planting Programme implemented by BPDASHL Jeneberang Saddang did not achieve optimal results because no formal follow-up agreement existed between the parties. Future collaboration should include written commitments and shared responsibilities between the management group, government agencies, NGOs and private actors to ensure continuity of rehabilitation and tourism development efforts.

h) Formulation of clear regulations on area boundaries (ST)

Mangrove forests hold substantial economic and ecological value. Arfiani et al. (2021a) estimated the total economic value of Balang Baru mangrove forest at approximately IDR 1,232,548,465 per year. This high value can attract external exploitation if boundaries are unclear. It is therefore necessary to establish regulations defining utilisation zones and conservation zones to prevent uncontrolled resource use and to protect ecological functions.

i) Promotion of unique tourism products (ST)

Established in 2018, the Mangrove Idaman area faced a decline in visitors during the COVID-19 pandemic (2019–2022) and increased competition from newly developed mangrove sites in 2024. Nevertheless, Balang Baru possesses unique biodiversity, including Oecophyllas maragdina (weaver ants), honeybees, mangrove crabs, spiders, wood geckos, green doves, mudskippers, monitor lizards and egrets. Nearby aquaculture ponds also offer distinctive scenery. Highlighting these attractions can create unique tourism products that differentiate Mangrove Idaman from other mangrove destinations in Jeneponto.

j) Establishment of guard posts and monitoring systems (WT)

The development of mangrove ecotourism must include strong monitoring mechanisms. Guard posts managed by the tourism group and supported by local volunteers can reduce illegal exploitation of the mangrove area. Community-based monitoring groups can ensure compliance with established regulations and maintain ecological integrity.

k) Design of effective promotional campaigns (WT)

Promotional campaigns are essential for attracting visitors and reinforcing site recognition. Collaboration among the management group, local government, and NGOs can produce effective advertisements and information materials that highlight the site’s ecological and educational value. According to Ferbita et al. (2020), social-media platforms such as instagram, facebook, tiktok and Youtube can be used for digital branding through high-quality visual content and short videos to strengthen the tourism image of Mangrove Idaman.

l) Formalisation of multi-stakeholder cooperation through MoU (WT)

The declining popularity of Mangrove Idaman emphasises the need for stronger cooperation among government, communities, private sectors, and related stakeholders. Establishing formal Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) will provide a legal framework for joint management, investment, and innovation. This measure can enhance governance, increase participation, and improve the sustainability of mangrove ecotourism in Balang Baru.

4. Conclusion

The study demonstrates that the utilisation of mangrove forest areas is not limited to tourism but encompasses a variety of economic and ecological functions that can be managed sustainably. To optimise the management of mangrove forest tourism, an integrated approach is required one that combines ecological, social, and economic considerations within a community-based framework.

The SWOT analysis identified several key strategies for improving mangrove tourism management in Balang Baru Village. These include utilising non-tourism zones for rehabilitation, developing mangrove education parks, creating official tourism websites, upgrading facilities and infrastructure, promoting research and publications, conducting regular training and awareness programmes, strengthening collaboration among stakeholders, establishing clear regulations for area use, promoting unique tourism products, setting up monitoring and guard posts, implementing effective promotional campaigns and formalising multi-stakeholder cooperation through Memoranda of Understanding (MoU).

Collectively, these strategies provide a comprehensive roadmap for enhancing the sustainability of the Mangrove Idaman tourism area. This implementation expected to increase the ecological resilience, while simultaneously improving welfare of local communities through the development of inclusive ecotourism. Moreover, our findings highlight that effective mangrove management depends on continuous collaboration between village institutions, local residents and external stakeholders, ensuring that governance, conservation and livelihood objectives are aligned in practice.

5. Author Contributions

The first author (SARS) contributed as compiler and data analyst based on the research results. The second author (ARYW) contributed methods to help interpret data and research results, and the third author (HM) contributed methods to help interpret data and article preparation.

6. Competing Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest throughout the entire research process.

7. Acknowledgements

The author would like to express his gratitude to the village government and the community of Balang Baru Village, Tarowang District, Jeneponto Regency for their participation and assistance during the research on the optimization of mangrove forest tourism management. The author would also like to express his gratitude to the Jeneponto regency government and several related stakeholders.

8. References

Adinugroho, G., & Sofiani, S. (2023). Analisis Strategi Pengelolaan Destinasi Wisata Taman Wisata Alam Mangrove Angke Kapuk Sebagai Destinasi Ekowisata Di Kota Jakarta Utara Guna Meningkatkan Minat Berkunjung Kembali. Jurnal Ilmiah Global Education, 4(3), 1800–1809. https://doi.org/10.55681/jige.v4i3.1245.

Arfiani, S., man, S., & Restu, M. (2021a). Optimal Mangrove Forest Management Based on Economic Value. International Journal of Science and Management Studies (IJSMS), 96–104. https://doi.org/10.51386/25815946/ijsms-v4i6p111

Arfiani, S., man, S., & Restu, M. (2021b). Optimal Mangrove Forest Management Based on Economic Value. International Journal of Science and Management Studies (IJSMS), 96–104. https://doi.org/10.51386/25815946/ijsms-v4i6p111

Ely, A. J., Tuhumena, L., Sopaheluwakan, J., & Pattinaja, Y. (2021). Strategi Pengelolaan Ekosistem Hutan Mangrove Di Negeri Amahai. TRITON: Jurnal Manajemen Sumberdaya Perairan, 17(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.30598/tritonvol17issue1page57-67

Ferbita, L. V., Setianti, Y., & Dida, S. (2020). Strategi digital branding Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia (LIPI) melalui media sosial. Acta Diurna: Jurnal Ilmu Komunikasi, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.20884/1.actadiurna.2020.12.2.2865

Hastuti, Y. D., & Salsabila, N. (2022). Intense work for mangrove planting, forest, and land rehabilitation efforts, and generating the coastal community economy in the pandemic era. Biological Environment and Pollution. https://doi.org/10.31763/bioenvipo.v2i2.607

Kasnir, M., Djafar, S., & Kaharuddin, K. (2021). Valuasi ekonomi dan strategi pengembangan wisata mangrove di Desa Balang Baru, Kecamatan Tarowang, Kabupaten Jeneponto. Journal of Indonesian Tropical Fisheries (JOINT-FISH), 4(2). https://doi.org/10.33096/joint-fish.v4i2.103.

Mappiasse, M. F., & Mukhlisa, A. N. (2024). Recognition and Analysis of Pest-Induced Damage in Mangrove Ecosystems: A Case Study in Maros Coastal Region. Jurnal Wasian, 11(2), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.62142/syae7z28

Mashuri, M., & Nurjannah, D. (2020). Analisis SWOT Sebagai Strategi Meningkatkan Daya Saing. JPS (Jurnal Perbankan Syariah), 1(1), 97-112. https://doi.org/10.46367/jps.v1i1.205

Mhatre, M. A. (2024). Role of Mangroves as Fishery Resource: A Systematic Review. Uttar Pradesh Journal of Zoology. https://doi.org/10.56557/upjoz/2024/v45i164285

Meirezaldi, O., Worokinasih, S., Fahrudi, A. N. L. I., Prafitri, R., Trisnawati, A., Saputra, R. B., Chien, J. M. S. (2024). Optimalisasi potensi ekosistem mangrove untuk pengembangan wisata berkelanjutan di Desa Patuguran. Community Development Journal: Jurnal Pengabdian Masyarakat, 5(6), 10937–10942. https://doi.org/10.31004/cdj.v5i6.37296.

Purwindiyanto, A., Meylani, E., Andika, R., & Nurfadilah, R. (2020). Potensi taman mangrove Pulau Pramuka sebagai destinasi edutourism (Potential of Mangrove Park, Pramuka Island as edutourism destination). Jurnal Hutan Tropis, 8(3), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.20527/jht.v8i3.9745.

Putri, A., Yasin, A., & Agustina, D. T. (2025). Literature Analysis: Local Community Involvement in Mangrove Forest Ecotourism Management in Indonesia. JURNAL RISET RUMPUN ILMU TANAMAN. https://doi.org/10.55606/jurrit.v4i1.6526

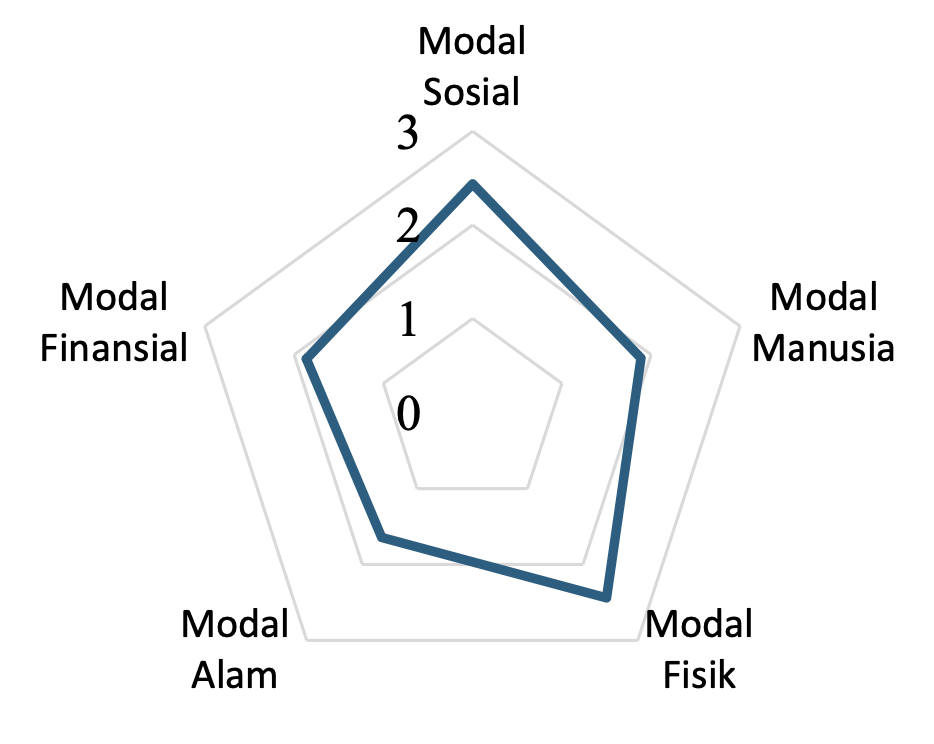

Sabar, A., Rusyid, E. I., Diana, F., Ansar, A., Annisa, N., Idzatilangi, W. I., & Agustiningrum, C. (2025). Livelihood Assets of Lantebung Mangrove Ecotourism Community. Jurnal Wasian, 10(02), 01–10. https://doi.org/10.62142/3w65rp54

Saputra, K. S. A., & Suniantara, I. K. P. (2023). Sistem Informasi e-Tourism Ekowisata Hutan Mangrove Se-bagai Media Promosi Pariwisata Bali Berbasis Android. JTIM : Jurnal Teknologi Informasi Dan Multimedia, 5(3), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.35746/jtim.v5i3.364

##submission.copyrightStatement##

##submission.license.cc.by4.footer##Copyright and License

All articles published in Wasian Journal are the property of the authors. By submitting an article to Wasian Journal, authors agree to the following terms:

-

Copyright Ownership: The author(s) retain copyright and full publishing rights without restrictions. Authors grant the journal the right to publish the work first and to distribute it as open access under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

-

Licensing: Articles published in Wasian Journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). This license allows others to share, copy, and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and adapt, remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided that proper credit is given to the original author(s) and the source of the material

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. -

Author's Rights: Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges and greater citation of published work.

-

Third-Party Content: If your article contains material (e.g., images, tables, or figures) for which you do not hold copyright, you must obtain permission from the copyright holder to use the material in your article. This permission must include the right for you to grant the journal the rights described above.

-

Reprints and Distribution: Authors have the right to distribute the final published version of their work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), provided that the original publication in Wasian Journal is acknowledged.

For the reader you are free to:

- Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format for any purpose, even commercially.

- Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially.

- The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms.

Under the following terms:

- Attribution — You must give appropriate credit , provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made . You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

- No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

Notices:

You do not have to comply with the license for elements of the material in the public domain or where your use is permitted by an applicable exception or limitation .

No warranties are given. The license may not give you all of the permissions necessary for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy, or moral rightsmay limit how you use the material.

##plugins.generic.recommendByAuthor.heading##

- Hananu Wisnu Wardana, Muthmainnah Muthmainnah , Hasanuddin Molo, Rahmat Ariandi, Community Perceptions and Preferences Toward Tourism Village Development in Kojadoi Village, East Alok Subdistrict, Sikka Regency, East Nusa Tenggara Province , Jurnal Wasian: 卷 10 期 02 (2023): December