Revealing Carbon Patterns Across Mangrove Density Variations Using Sentinel-2 NDVI

Abstract

Mangrove ecosystems play a crucial role in maintaining the balance of coastal ecosystems and mitigating climate change due to their ability to absorb and store carbon. This study aims to estimate carbon stocks across different mangrove density levels on Bangko-bangkoang Island, Pangkep Regency, South Sulawesi Province. The methods employed include Sentinel-2 imagery analysis using the Google Earth Engine platform to identify vegetation density based on the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and estimate carbon stocks using an allometric model and field data. The Sentinel-2 image analysis revealed that the mangrove vegetation cover on Bangko-bangkoang Island spans 16.04 ha. NDVI results show that mangroves in the low-density class cover 8.97 ha (56%), the medium-density class covers 3.71 ha (23%), and the high-density class covers 3.34 ha (21%). Field surveys confirmed the presence of three mangrove species on the island: Rhizophora mucronata, Rhizophora stylosa, and Sonneratia alba. Regression analysis conducted to assess the relationship between NDVI values and carbon stocks revealed the best model as an exponential function with the equation y = 0.0043e(11.726x), yielding a coefficient of determination (R²) of 0.683. The average carbon stock for the low-density class is 22.35 tons C/ha, for medium density is 67.1 tons C/ha, and for high density is 111.85 tons C/ha. These findings emphasize the important role of mangroves in climate change mitigation and provide scientific evidence for mangrove conservation efforts, particularly in enhancing vegetation density to optimize carbon storage.

1. Introduction

Mangroves are tropical coastal ecosystems that play a very important role in climate change mitigation, particularly as carbon sinks and reservoirs (Mutahharah et al., 2024). One of their main functions is to provide protection from tropical storms. Mangroves not only protect coastlines from abrasion, waves, and storms, but also support various ecological functions such as providing habitats for coastal fauna and boosting the economy of local communities. In addition, mangrove forests also play a role in carbon sequestration and storage, which contributes to reducing the increase in carbon emissions in the atmosphere. Based on research (Z.A et al., 2024). The tropical coastal ecosystems that can absorb the most carbon dioxide (CO2) are mangrove forests. Mangrove forests have the capacity to store up to four times as much carbon as other tropical forests (Basyuni et al., 2023). However, development pressures, land conversion for agriculture and aquaculture, and environmentally unfriendly extraction have caused a fall in the area and quality of mangroves. Conservation efforts, such as mangrove ecosystem rehabilitation and mangrove area protection in South Sulawesi, demonstrate the importance of accurate spatial data as a basis for planning and monitoring mangrove management policies (Zeng et al., 2021). Given the global ecological importance of mangroves, accurate and site-specific assessments—particularly in regions experiencing ecological pressure—are increasingly needed to support effective conservation and management. Although the role of mangroves in climate change mitigation, particularly in carbon storage, has been extensively studied, there remains a lack of quantitative data on the distribution and carbon stock of mangroves, particularly in large and remote coastal areas. Previous studies have primarily relied on conventional field surveys, which are time-consuming and costly. However, with recent technological advancements, remote sensing techniques using Google Earth Engine (GEE) have shown potential to address these limitations (De Clerck et al., 2024), o address these limitations, this study integrates GEE with allometric modeling to produce accurate, efficient, and large-scale carbon stock estimates.

Pangkep Regency is one of the regencies in South Sulawesi, most of which is covered by sea. One of the mangrove ecosystems in Pangkep Regency is located on Bangko-bangkoang Island. This area is known for its relatively intact mangrove ecosystem, which has high ecological value, especially as a blue carbon sink. The uniqueness of this island lies in the dominance of naturally regenerated mangroves. However, its current condition is under threat due to the expansion of fish. ponds, which will gradually reduce the ecosystem's function. Therefore, a scientific, technology-based approach is required to map and monitor mangrove density and carbon stocks on Bangko-bangkoang Island, ensuring that management interventions are based on accurate spatial information.

The approach used combines two methods, namely remote sensing technology based on Google Earth Engine (GEE) and Allometric Modeling (Pham et al., 2019). GEE is a cloud-based computing platform specifically designed for large-scale remote sensing data processing and analysis (Puspitasari et al., 2024). In addition, GEE's data processing capabilities are very efficient in terms of time and cost management compared to conventional field survey methods (Fadillah et al., 2023). Therefore, this research is important to obtain data on the distribution of mangrove density on a large scale and to improve the accuracy of carbon biomass calculations.

2. Method

1) Research Location

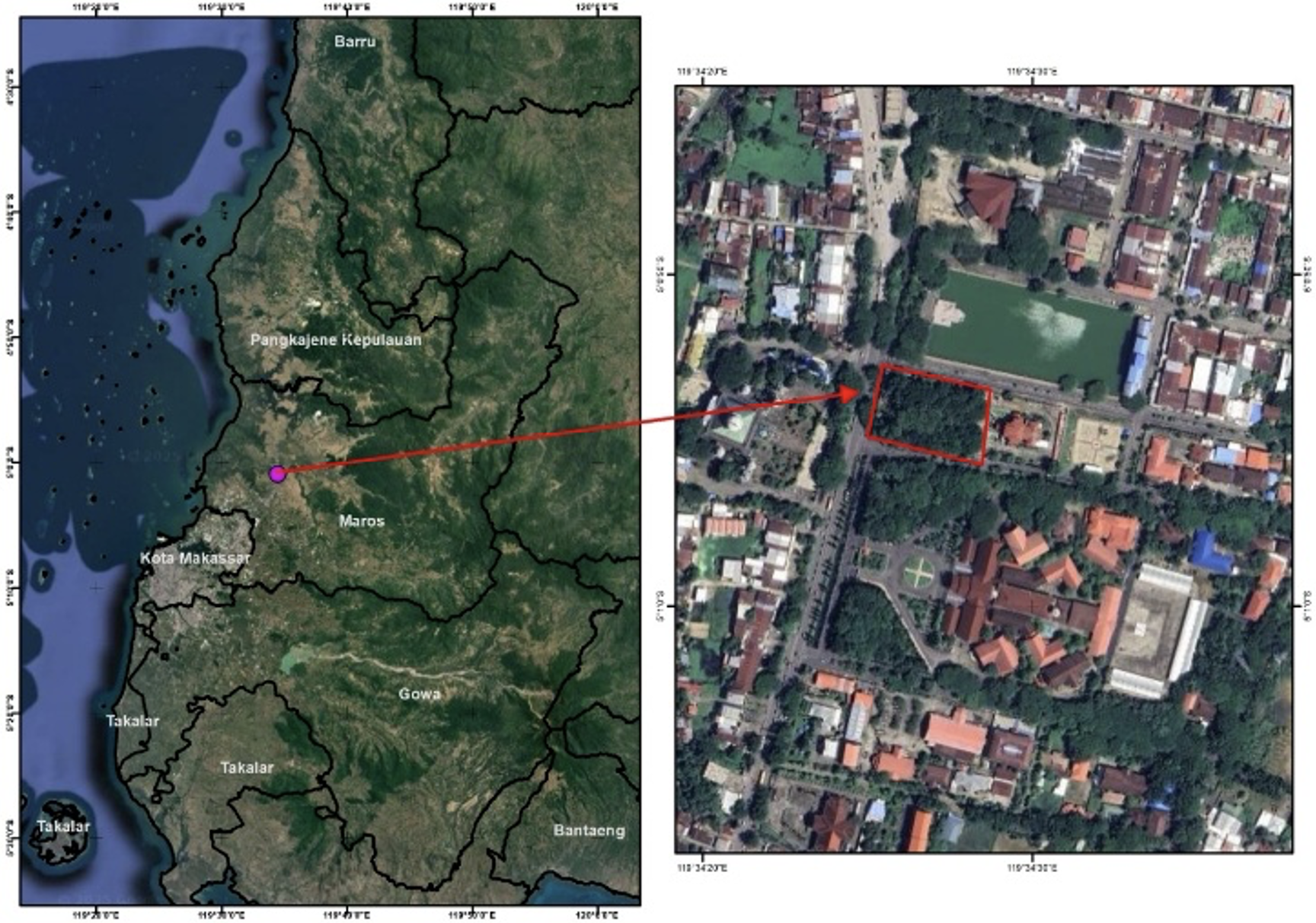

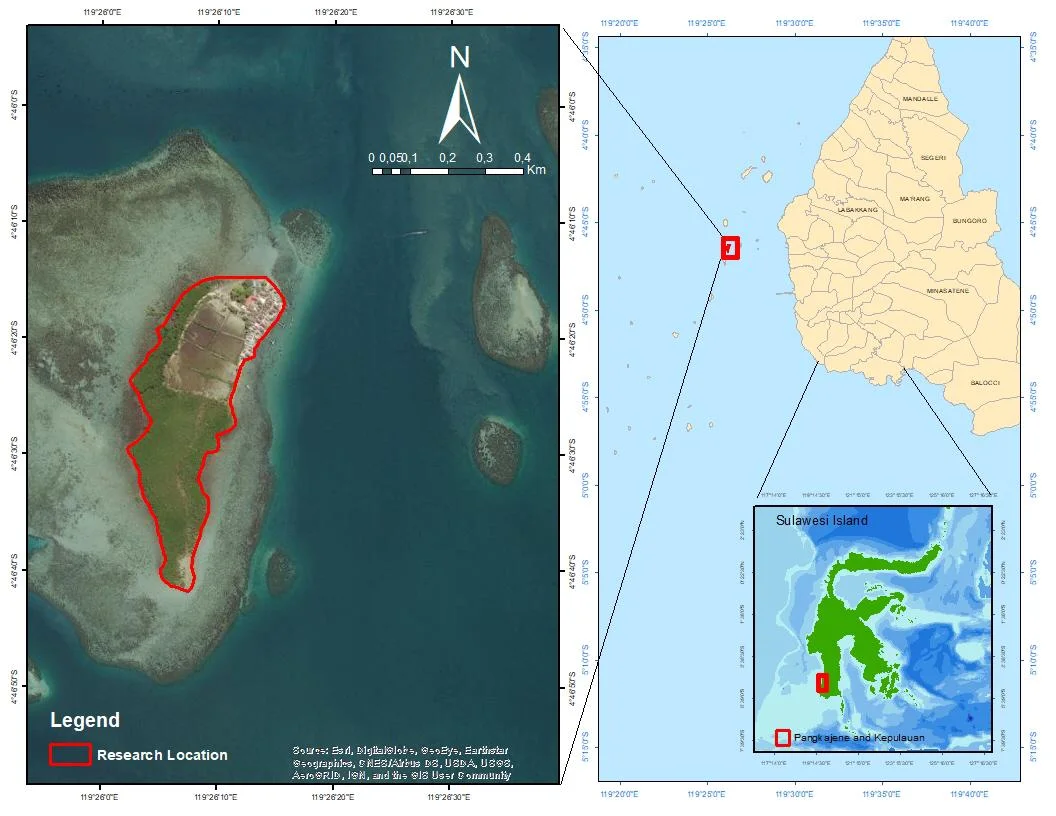

This study conducted in Bangko-bangkoang Island, Mattiro Uleng Village, Pangkajene Islands Regency, South Sulawesi (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of Study Area

2) Tool and Materials

The tools used in this study were a GPS (Global Positioning System) receiver to locate ground check points in the field. Tally sheets and writing instruments were used to record the results of the activities. A measuring tape/phiband was used to measure tree diameters in the field. A roll meter was used to measure plot distances. Rope was used to mark the boundaries of each plot. The materials used in this research were data in the form of Sentine-2 Level 2A images with a spatial resolution of 10 meters, downloaded from the website https://earthengine.google.com/. Land cover data by ministry of forestry.

3) Research Procedure

· Image Pre-processing

Image pre-processing is performed to improve image quality by reducing the effects of atmospheric disturbances and consists of image cropping, cloud filtering, and image correction. Image cropping is intended to focus image processing on the area to be processed and reduce the image size so that image processing is more efficient. Cloud filtering is performed to find images with the lowest cloud cover within a specified time period in order to minimize clouds covering the study area.

· NDVI Analysis

At this stage, the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) algorithm is applied to produce a visual display of the mangrove area. The NDVI results will be used to classify the mangrove area. The classification of the mangrove area is adjusted to the spectral characteristics of the red band (visible red) absorbed by leaf chlorophyll and the near-infra-red band (NIR) that reflects the leaf tissue structure (Larekeng et al., 2024). The combination of these two bands produces a vegetation density index value. In this study, mangrove density classification was determined based on the NDVI algorithm (Semedi et al., 2023). The formula applied is as follows:

\( \displaystyle \mathrm{NDVI}=\frac{\mathrm{NIR}-\mathrm{Red}}{\mathrm{NIR}+\mathrm{Red}} \)

Explanation:

NIR = spectral reflectance value of the NIR band

R = spectral reflectance value of the red band

Futhermore, to determine the mangrove area, we refered to the land cover data provided by ministry of forestry year of 2024.

Field data collection was conducted using purposive sampling, considering accessibility and the mangrove area. According to the Geospatial Information Agency (Badan Infomasi Geospasial, 2014) the number of sample plots required for the proportional mangrove area is a minimum of 20 sample plots.

This method was used by researchers to achieve specific research objectives and was based on certain considerations, namely density class levels. The selection of field plot sampling points was conducted using purposive sampling, based on mangrove density levels measured using NDVI. The sample plot size was in accordance with Indonesian National Standard Number 7724/2019, based on measurements and calculations of terrestrial carbon stocks, with a size of 20 x 20 meters (m) in a square shape. To identify mangrove species and calculate carbon stocks, an allometric equation was used to estimate biomass.

To determine the mangrove density value, the calculation results from NDVI were used. Then, the NDVI class values were reclassified into 5 classes. The evaluation table of mangrove density levels based on NDVI values is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. NDVI classification for vegetation density

Source: Larekeng et al, 2024

4) Data Analysis

- Above-ground biomass (AGB) calculation

Above-ground biomass (AGB) calculations Biomass values are calculated using an allometric model approach to obtain the mangrove AGB carbon stock value, as shown in the following table of equations:

Table 2. Allometric equations for several types of mangrove stands

Thus, B refers to biomass (kg) and DBH (cm). Carbon stock values are calculated using biomass values in accordance with SNI No. 7724 of 2019 concerning land-based carbon stock measurement and calculation by using equation below :

C = B x % C organic (2)

C is the carbon content of biomass (kg), BoV is the total biomass (kg), and % organic C is the percentage value of carbon stocks, which is 0.47 (Badan Standardisasi Nasional, 2011)

- Carbon Stock Calculation

Carbon stock calculations are made based on a statistical regression model. The relationship between aboveground carbon stocks and NDVI values is analyzed using a mathematical equation with regression model (Jin et al., 2020). The regression model used in this study:

Linear Y = 𝑎 + 𝑏𝑋 (3)

Eksponesial Y = 𝑎𝑒𝑏𝑥 (4)

Logaritmik Y = 𝑎 + 𝑏 𝐼𝑛 𝑋 (5)

Polinominal Y = 𝑏0 + 𝑏1𝑋+ 𝑏2𝑋2+ 𝑏3𝑋3+....𝑏𝑛𝑋𝑛 (6)

Y is carbon stocks (tons C/ha), X is the Vegetation Index value, and a and b are coefficient values.

3. Result and Discussion

1) Vegetation Composition of Mangrove Species on Bangko-bangkoang Island

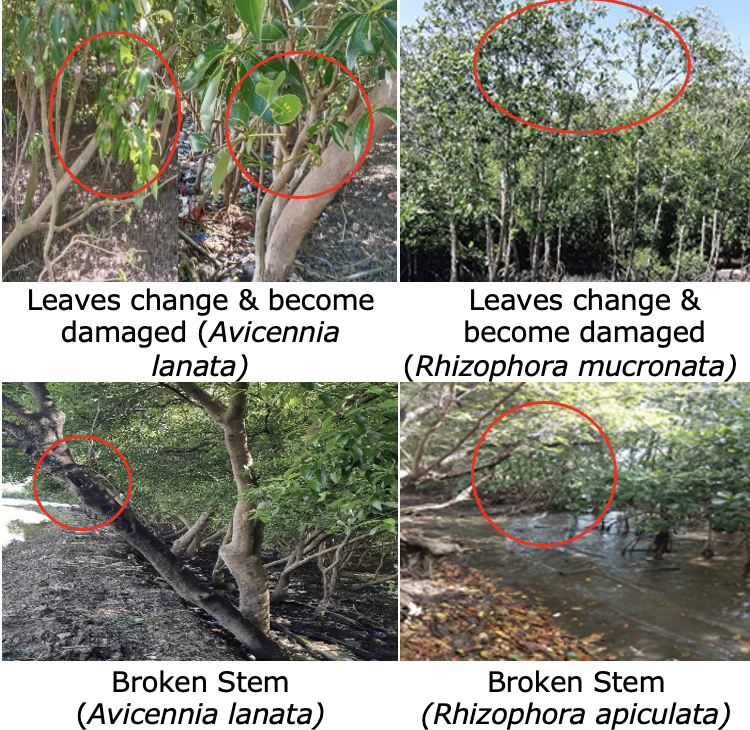

The interpretation of Sentinel-2A imagery recorded on August 8, 2025 shows that the mangrove coverage area on Bangko-bangkoang Island, Pangkep Regency, reaches 16.04 ha. The visualization of the 2024 mangrove stand interpretation results is presented in Figure 3. In addition, field observations were also conducted to ensure the accuracy of the NDVI analysis results for various types of mangroves at the research site. Based on the results of field observations at the observation site, it was found that mangroves generally have a high density. Three mangrove species were identified, namely Rhizophora mucronata (1077), Rhizophora stylosa (338), and Sonneratia alba (48). Rhizophora mucronata is the most dominant and most abundant species in various observation plots. Research (Faizal et al., 2023) shows that Rhizophora mucronata can grow and adapt well to deep, thick, muddy substrates because it has anchor-like prop roots that can firmly anchor themselves into the ground. Rhizophora mucronata, or often called red mangrove, has cool adaptations to survive in challenging coastal environments. With its distinctive prop roots, this tree can stand firmly in muddy substrates that are often flooded by high tides. These roots also help improve soil structure and prevent erosion (Karthi et al., 2020).

Research by (Kadir et al., 2025) on the structure and composition of mangroves in Bonto Bahari and Ampekalle shows that Rhizophora mucronata, which is dominant on Bangko-bangkoang Island, is more effective at storing carbon than other mangrove species that are more affected by human activity. These results are in line with findings on Bangko-bangkoang Island, where Rhizophora mucronata shows very high carbon potential compared to Sonneratia alba and Rhizophora stylosa, which are more sensitive to environmental changes. Currently, the condition of the mangrove ecosystem on Bangko-bangkoang Island is deteriorating due to the exploitation of mangrove wood for fuel and construction, and marine debris also poses a significant threat to the sustainability of mangrove forests on the island. These activities have caused a decline in more sensitive mangrove species, such as Sonneratia alba and Rhizophora stylosa. According to (Arfan et al., 2024), although Bangko-bangkoang Island has great potential to be managed as an ecotourism area, human activities such as land use for aquaculture and the harvesting of mangrove wood for local needs threaten the sustainability of this ecosystem. The decline in mangrove quality, due to overexploitation and land conversion, causes habitat damage that disrupts the mangroves' ability to store carbon and provide other ecosystem services.

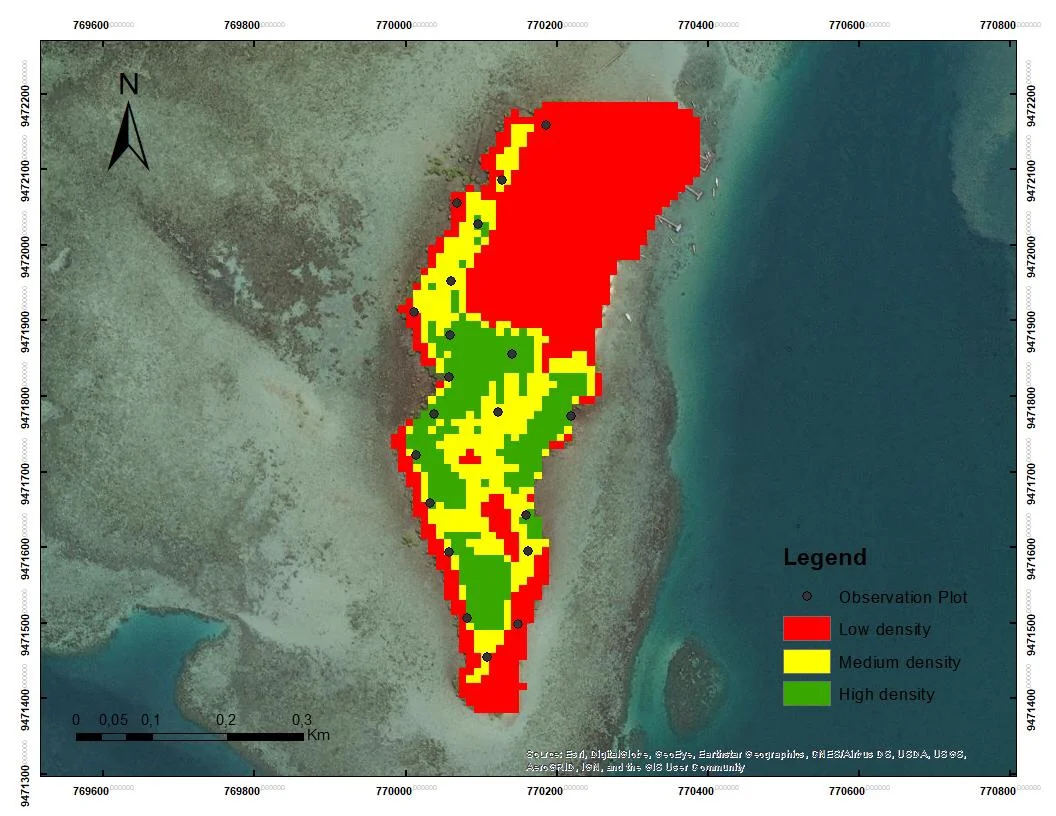

2) Mangrove Density Classification Based on Normalized Difference Vegetation Index

Based on the analysis of Sentinel-2 NDVI imagery on Bangko-bangkoang Island in Pangkep Regency, the value range is -0.19 to 0.87. This NDVI value range indicates that the more negative the pixel value, the lower the vegetation density in the area. Specifically, NDVI utilizes a combination of spectral reflectance in the red and near-infrared (NIR) band. The difference between the reflectance of these two channels is sensitive to the presence and condition of vegetation, making NDVI effective in distinguishing areas with different vegetation densities. Mangrove forests with high vegetation density, such as those found on Bangko-bangkoang Island, will appear darker green on the NDVI and indicating good conditions, the NDVI results can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 2. Mangrove Density Map

According to research (Basheer et al., 2019) in identifying mangrove species, NIR spectral data is highly sensitive to water content and vegetation leaf structure. The denser the vegetation, the More light is reflected in the NIR spectrum, making NDVI a more effective tool for detecting vegetation density and condition. Mangroves have the highest reflectance in the NIR spectral region, followed by the BLUE and RED spectral, while the GREEN and SWIR spectra do not show significant reflection. The distribution of mangrove density is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Mangrove Density Distribution

Mangrove forests with multiple strata, such as Rhizophora mucronata, which has a greater height and trunk diameter, will produce a brighter and denser NDVI. According to (Mappiasse et al., 2022), NDVI images of such areas will appear dark green, indicating healthy forest conditions. Forests with more complex tree strata, including large trees, shrubs, and undergrowth, typically show higher NDVI values. The color sharpness in NDVI images not only reflects tree density but also indicates higher vegetation diversity (Faizal et al., 2023). Mangrove forests with greater species diversity and layered tree strata, such as Rhizophora mucronata, tend to appear greener and denser. Similar research by (Arfan et al., 2024) also suggests that mangrove species diversity can influence NDVI values. For example, Rhizophora mucronata, which is dominant in the region, generally yields higher NDVI values compared to other species such as Sonneratia alba.

Table 3 shows the distribution of mangrove density in Pulau Bangko-bangkoang, Pangkep Regency, based on NDVI image analysis. Of the total 16.04 ha, the area is divided into three density classes: low, moderate, and high. The low density class covers 8.97 ha or 56% of the total area, indicating that most of the mangrove area has low density. The moderate density class accounts for 3.71 ha or 23%, showing that a significant portion of the mangrove area has moderate density. Meanwhile, the high density class spans 3.34 ha or 21%, indicating that areas with very dense mangrove vegetation are limited in this region.

These results show that most of the area on Bangko-bangkoang Island has low to moderate mangrove density, with only a few areas having high density. This may be influenced by environmental factors such as salinity, water depth, and other physical conditions that affect mangrove growth (Chowdhury et al., 2023). This study also emphasizes the importance of the role of high-density mangroves in storing more carbon, because the denser the mangrove vegetation, the greater the carbon storage capacity of the ecosystem (Kang et al., 2024).

3) Above ground biomass (AGB)

Biomass calculations using allometric equations were then used to determine the carbon stock in each observation plot. In assessing carbon stocks, it was assumed that 47% of the total biomass consisted of carbon. Carbon stocks are usually measured in tons of carbon per hectare (ton C/ha).

Table 4. Average DBH, Average Height, Biomass, and Carbon per Species

Table 4 presents data on above-ground biomass (AGB) and carbon stocks of three different mangrove species, namely Rhizophora mucronata, Rhizophora stylosa, and Sonneratia alba, observed based on the parameters of diameter at breast height (DBH), tree height, biomass, and carbon stocks. Rhizophora mucronata has an average DBH of 8.74 cm and an average height of 3.97 meters, with a biomass of 51.20 tons/ha and carbon stocks reaching 24.06 tons/ha. Rhizophora stylosa, despite having a smaller DBH (6.77 cm) and lower height (2.83 meters), showed higher biomass of 25.30 tons/ha and carbon stocks of11.89 tons/ha. Meanwhile, Sonneratia alba had an average DBH of 7.30 cm and a height of 2.91 meters, but its biomass and carbon stock were much lower, at 10.14 tons/ha and 4.77 tons/ha, respectively.

Research on structural variables of mangrove stands such as basal area, diameter at breast height (DBH), and average height affects above-ground biomass and carbon storage potential in mangrove stands (Aye et al., 2023). In other words, the larger the size and height of mangrove trees, the higher the biomass and capacity to store carbon (Ulqodry et al., 2025)

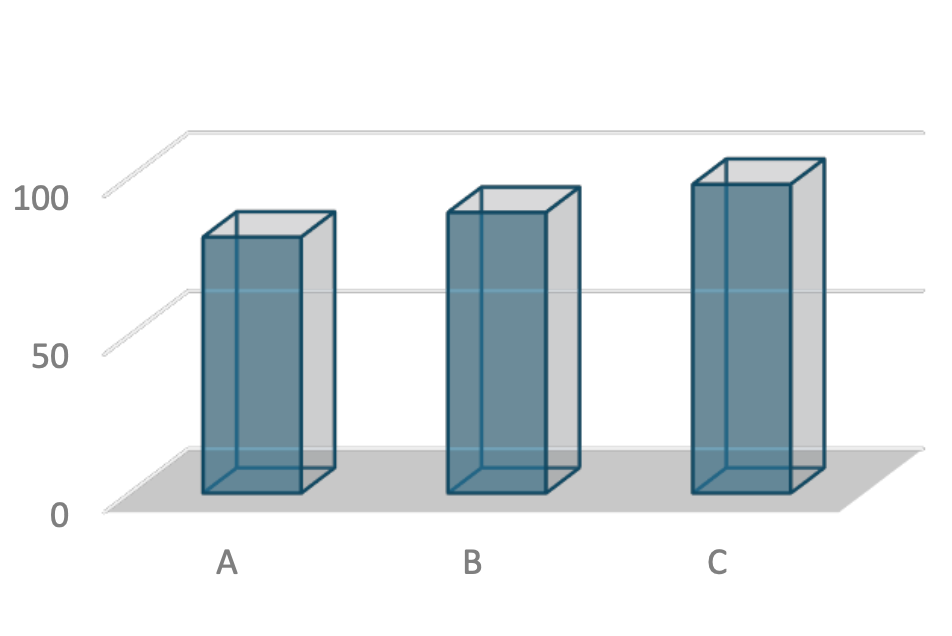

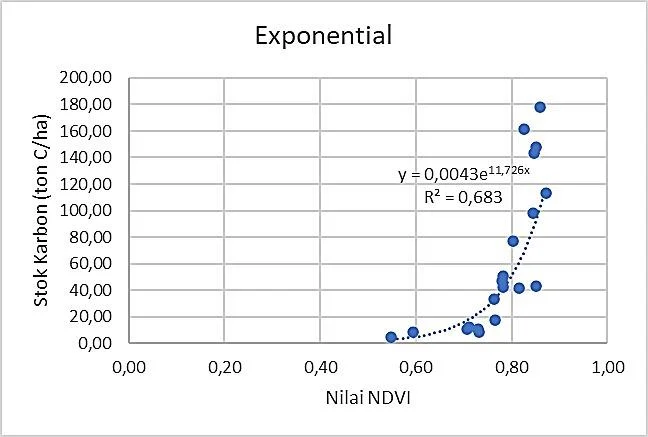

4) Carbon Stock Estimation Model

The carbon stock estimation model was generated by analyzing NDVI value and carbon stock data from field survey through a regression model analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel. This model was developed using a regression model between variable X (vegetation index value) and variable Y (carbon value). The regression analysis results presented in Figure 3 show an exponential relationship between the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) value and biomass. The regression model obtained is y = 0.0043e(11.726x) with R² = 0.683. This R² value indicates that NDVI is able to explain of the variation in biomass, with the remainder being influenced by other factors such as vegetation type, stand age, canopy density, and local environmental conditions.

Figure 3. Mangrove Density Map

This relationship indicates a positive correlation between the level of vegetation greenness captured by satellite imagery and biomass accumulation in the field. The index results used have their own characteristics. The pixel values generated from the processing of the index transformation will be tested in the field to obtain the correlation value (r). The stronger the relationship, the closer the value (r) will be to 1. In addition, based on the graph, there is a positive correlation between NDVI values and mangrove carbon stocks stored in tons of carbon per hectare (ton C/ha). Meanwhile, research explains that NDVI is influenced by canopy cover. The higher the canopy cover, the higher the NDVI value or the more positive the correlation. (Hendrawan et al., 2018) emphasizes that although NDVI can be used to measure the percentage of mangrove canopy cover, its use to measure mangrove tree density has limitations. This is due to the sensitivity of NDVI to factors such as soil moisture and other types of vegetation that can affect the results of mangrove tree density measurements.

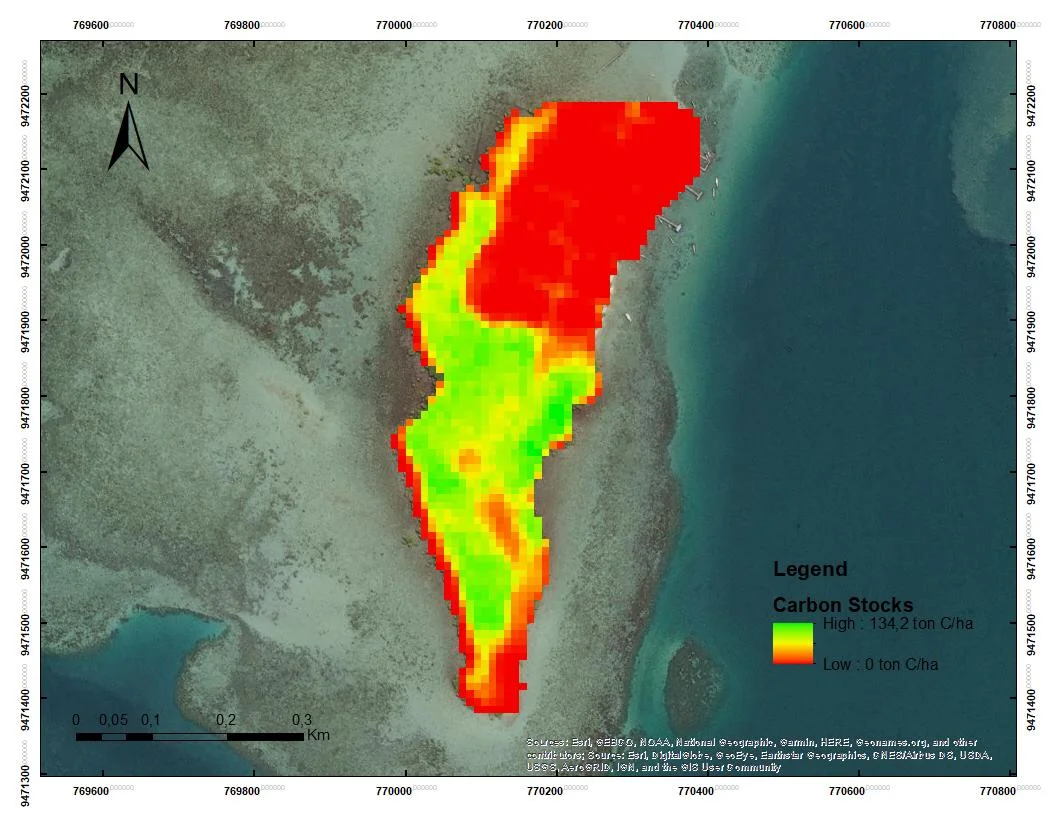

Table 5. Carbon stock Values in Bangko-bangkoang Island Mangrove Forest

Figure 4. Carbon Stock Map

The table provides data on the relationship between mangrove density levels and carbon stock, showing the minimum, maximum, and average carbon stock (in tons of carbon per hectare) for each density category. For low-density mangroves, the minimum carbon stock is 44.7 tons C/ha, while the maximum is 22.35 tons C/ha, and the average carbon stock is recorded as 0 tons C/ha. This suggests that areas with low mangrove density have a relatively low or negligible carbon storage capacity. In contrast, medium-density mangroves show a minimum carbon stock of 89.5 tons C/ha, a maximum of 67.1 tons C/ha, and an average of 44.7 tons C/ha, indicating a moderate carbon storage potential. For high-density mangroves, the minimum carbon stock is 134.2 tons C/ha, the maximum is 111.85 tons C/ha, and the average is 89.5 tons C/ha, reflecting the highest capacity for carbon storage. Overall, this table illustrates how higher mangrove density correlates with greater carbon storage, highlighting the importance of dense mangrove ecosystems in carbon sequestration.

The research results show that carbon calculations using an allometric model are aimed at field measurement analysis (species-based). Meanwhile, NDVI is used as a variable in the model to estimate carbon stocks across the entire study area. There is no direct correlation between mangrove species and NDVI, but the average carbon stock values are linked with NDVI to conduct analysis/estimation of regional carbon stocks through remote sensing.

Comparison with previous studies conducted by (Khan et al., 2020) shows a similar approach in using NDVI for vegetation density estimation; however, they used a different allometric model or more limited field data. Their study confirmed that NDVI can be used as a variable to predict carbon stocks in mangrove ecosystems, although it focused more on broader areas without considering species variability. Otherwise, this study integrate carbon calculations based on specific mangrove species, offering a deeper insight into the contribution of each species to the overall carbon stock.

Meanwhile, (Fahlevi & Darmawan, 2020 ) utilized field data and low-resolution remote sensing data, whereas this study takes advantage of Sentinel-2 imagery with higher resolution, enabling more accurate analysis of mangrove density and regional carbon estimation. This research contributes to the development of more integrated methods between species-based field data and remote sensing, enabling more comprehensive mangrove carbon stock analysis. Consequently, the results of this study expand existing methodologies and provide a more holistic view of carbon distribution in mangrove ecosystems, supporting mangrove ecosystem management and climate change mitigation. The findings from this research can be used as a foundation for policy decision-making, as well as for long-term monitoring of the role of mangrove ecosystems in carbon sequestration.

4. Conclusion

This study shows that mangrove forests on Bangko-bangkoang Island have significant potential for carbon storage, which depends on the density of mangrove vegetation. Through the use of Google Earth Engine (GEE)-based remote sensing technology and allometric models, this study successfully estimated carbon stocks in various classes of mangrove density, from very low to very high. The results of the analysis show that the higher the mangrove density, the greater the capacity of the ecosystem to store carbon. At a very low density level, carbon stocks were recorded at around 13.43 tons C/ha, while at high densities, carbon stocks could reach 120.8 tons C/ha. The use of the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) algorithm in this study proved to be effective for mapping the distribution of mangrove density and accurately estimating carbon stocks on a large scale. The regression model built showed a significant positive relationship between NDVI values and carbon stocks, with an R² of 0.68, indicating that NDVI was able to explain most of the variation in carbon stocks.

5. Author Contributions

The contribution of the first author is as a compiler and formulator of scientific methodology and assists in collecting data in the field, while the contribution of the second and third authors is to assist the first author in analyzing field data and assisting in revising the writing of scientific articles, the fourth contribution is to assist in revising the editing of scientific articles

6. Competing Interests

The authors have declared that there are no competing interests.

7. Acknowledgements

The author would like to express his gratitude to the people of Bangko-bangkoang Island, the maritime intellectual forum, and the village government of Mattiro Uleng, Liukang Tupabbiring Utara Subdistrict, Pangkajene and Kepulauan Regency for their permission and support, which enabled this research to be carried out successfully.

8. References

Analuddin, K., Kadidae, L. O., Yasir Haya, L. O. M., Septiana, A., Sahidin, I., Syahrir, L., Rahim, S., Fajar, L. O. A., & Nadaoka, K. (2020). Aboveground biomass, productivity and carbon sequestration in rhizophora stylosa mangrove forest of southeast sulawesi, indonesia. Biodiversitas, 21(4), 1316–1325. https://doi.org/10.13057/biodiv/d210407

Arfan, A., Maru, R., Nyompa, S., Sukri, I., & Juanda, M. F. (2024). Analysis of Mangrove Density using NDVI and Macrobenthos Diversity in Ampekale Tourism Village South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Jurnal Sylva Lestari, 12(2), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.23960/jsl.v12i2.788

Aye, W. N., Tong, X., Li, J., & Tun, A. W. (2023). Assessing the Carbon Storage Potential of a Young Mangrove Plantation in Myanmar. Forests, 14(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/f14040824

Basheer, M. A., El Kafrawy, S. B., & Mekawy, A. A. (2019). Identification of mangrove plant using hyperspectral remote sensing data along the red sea, Egypt. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology and Fisheries, 23(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejabf.2019.25932

Basyuni, M., Pandiangan, P., Amelia, R., Al Mustaniroh, S. S., Larekeng, S. H., Sumarga, E., Slamet, B., & Arifanti, V. B. (2023). Carbon stock potential in rehabilitated mangrove in Lubuk Kertang Village, North Sumatra, Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1277(1). https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1277/1/012005

Badan Infomasi Geospasial, Peraturan Kepala Badan Informasi Geospasial Nomor 3 Tahun 2014 tentang Pedoman Teknis Pengumpulan dan Pengolahan Data Geospasial Mangrove. (2014).

Badan Standardisasi Nasional. (2011). Pengukuran dan penghitungan cadangan karbon-Pengukuran lapangan untuk penaksiran cadangan karbon hutan (Ground based forest carbon accounting). www.bsn.go.id

Chowdhury, A., Naz, A., Sharma, S. B., & Dasgupta, R. (2023). Changes in Salinity, Mangrove Community Ecology, and Organic Blue Carbon Stock in Response to Cyclones at Indian Sundarbans. Life, 13(7), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13071539

De Clerck, E., D.Kovács, D., Berger, K., Schlerf, M., & Verrelst, J. (2024). Optimizing hybrid models for canopy nitrogen mapping from Sentinel-2 in Google Earth Engine. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 218, 530–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2024.11.005

Fadillah, M. A., Bashit, N., Qoyimah, S., Susilo, H., & Apriyanti, D. (2023). Analisis Pendugaan Stok Karbon Vegetasi Dengan Penginderaan Jauh Menggunakan Metode Light Use Efficiency di Hutan Penggaron, Kota Ungaran Kabupaten Semarang Provinsi Jawa Tengah. Elipsoida : Jurnal Geodesi Dan Geomatika, 6(1), 32–43. https://doi.org/10.14710/elipsoida.2023.18829

Fahlevi, F., & Darmawan, S. (2020). Estimasi Biomassa Mangrove Dengan Data Landsat Multitemporal Pada Google Earth Engine. Jurnal Online Institut Teknologi Nasional, 1–7. https://eproceeding.itenas.ac.id/index.php/ftsp/article/view/347

Faizal, A., Mutmainna, N., Amran, M. A., Saru, A., Amri, K., & Nessa, M. N. (2023). Application of NDVI Transformation on Sentinel 2A Imagery for mapping mangrove conditions in Makassar City. Akuatikisle: Jurnal Akuakultur, Pesisir Dan Pulau-Pulau Kecil, 7(1), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.29239/j.akuatikisle.7.1.59-66

Hendrawan, H., Gaol, J. L., & Susilo, S. B. (2018). Studi kerapatan dan perubahan tutupan mangrove menggunakan citra satelit di Pulau Sebatik, Kalimantan Utara (Study of density and change of mangrove cover using satellite imagery in Sebatik Island, North Borneo). Jurnal Ilmu dan Teknologi Kelautan Tropis, 10(1), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.29244/jitkt.v10i1.18595

Jin, X., Li, Z., Feng, H., Ren, Z., & Li, S. (2020). Deep neural network algorithm for estimating maize biomass based on simulated Sentinel 2A vegetation indices and leaf area index. The Crop Journal, 8(1), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cj.2019.06.005

Kadir, A., Rukminasari, N., Kudsiah, H., & Yunus, B. (2025). Comparison Of Structure And Composition Of Mangrove Types In Bonto Bahari And Ampekalle Area, Maros Regency. Jurnal Ilmu Kelautan, 11(1), 12–18.

Kang, L., Huamei, H., Ran, Y., Shengpeng, Z., Di, D., & Bo, P. (2024). Carbon storage potential and influencing factors of mangrove plantation in Kaozhouyang, Guangdong Province, South China. Frontiers in Marine Science, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1439266

Karthi, S., Uthirarajan, K., Manohar, V., Venkatesan, M., Chinnaperumal, K., Vasantha-Srinivasan, P., & Krutmuang, P. (2020). Larvicidal Enzyme Inhibition and Repellent Activity of Red Mangrove Rhizophora mucronata (Lam.) Leaf Extracts and Their Biomolecules against Three Medically Challenging Arthropod Vectors. Molecules, 25(17). 3844; https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25173844

Khan, K., Iqbal, J., Ali, A., & Khan, S. N. (2020). Assessment of sentinel-2-derived vegetation indices for the estimation of above-ground biomass/carbon stock, temporal deforestation and carbon emissions estimation in the moist temperate forests of pakistan. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research, 18(1), 783–815. https://doi.org/10.15666/aeer/1801_783815

Komiyama, A., Poungparn, S., & Kato, S. (2005). Common allometric equations for estimating the tree weight of mangroves. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 21(4), 471–477. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467405002476

Kusmana, C., Hidayat, T., Tiryana, T., Rusdiana, O., & Istomo. (2018). Allometric models for above- and below-ground biomass of Sonneratia spp. Global Ecology and Conservation, 15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00417

Larekeng, S. H., Nursaputra, M., Mappiasse, M. F., Ishak, S., Basyuni, M., Sumarga, E., Arifanti, V. B., Aznawi, A. A., Rahmila, Y. I., Yulianti, M., Rahmania, R., Mubaraq, A., III, S. G. S., Ali, H. M., & Yeny, I. (2024). Estimation of mangrove carbon stocks using unmanned aerial vehicle over coastal vegetation. Global Journal of Environmental Science and Management, 10(3), 1133–1150. https://doi.org/10.22034/gjesm.2024.03.13

Mappiasse, M. F., Djafar, M., & Asra, R. (2022). Distribution of mangrove health in the coastal area of Maros Regency in 2021 based on Sentinel-2 satellite imagery Sebaran kesehatan mangrove di wilayah pesisir Kabupaten Maros tahun 2021 berdasar Citra Satelit Sentinel-2. Jurnal Penelitian Kehutanan Wallacea, 11(2), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.18330/jwallacea.2022.vol11iss2pp165-179

Mutahharah, M., Alamsyah, R., Azizah, R., & Akram, A. (2024). Estimation of carbon content and carbon uptake in leaves, roots and soil in the mangrove coast of North Sinjai, Sinjai Regency. Jurnal Hutan Tropika, 19(2), 284–293. https://doi.org/10.36873/jht.v19i2.16815

Pham, T. D., Yokoya, N., Bui, D. T., Yoshino, K., & Friess, D. A. (2019). Remote sensing approaches for monitoring mangrove species, structure, and biomass: Opportunities and challenges. Remote Sensing.11(3). 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11030230

Puspitasari, R. F., Aisyah, Usnil Khotimah, Mahadika Rifka Nugraha, Ali Dzulfigar, Khairani Putri Marfi, Danik Septianingrum, Rahmat Asy’ari, Rahmat Pramulya, Neviati Putri Zamani, & Yudi Setyawan. (2024). Development of Spatial Platform Based Earth Engine Apps for Mangrove Carbon Stock: Case Study in Serang Coastal Zone, Banten Province. CELEBES Agricultural, 4(2), 140–154. https://doi.org/10.52045/jca.v4i2.746

Semedi, B., Marjono, M., Savitri, L. E., Hikmawati, V. F., Bayuaji, G. D. A. P., Syam, N. D. S., & Diza, N. F. (2023). Pemanfaatan Google Earth Engine untuk memantau perubahan luasan hutan mangrove di Probolinggo: Application of Google Earth Engine for monitoring mangrove forest changes in Probolinggo. JFMR (Journal of Fisheries and Marine Research, 7(2), 79–87. https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.jfmr.2023.007.02.9

Ulqodry, T. Z., Raihan, M., Muhtadi, Sarno, Hendri, M., Apri, R., Putri, W. A. E., & Aryawati, R. (2025). Carbon Stock and Potential for Carbon Absorption by Mangrove Forests on Maspari Island: The Outermost Small Island in South Sumatra. Jurnal Sylva Lestari, 13(2), 519–536. https://doi.org/10.23960/jsl.v13i2.1095

Z.A, S. A., Puna, S. H., Lestariningsih, W. A., & Rahman, I. (2024). Perbandingan Jumlah Cadangan Karbon Mangrove Aboveground dan Belowground di Gili Petagan, Sambelia, Lombok Timur. Journal of Marine Research, 13(2), 301–310. https://doi.org/10.14710/jmr.v13i2.43504

Zeng, Y., Friess, D. A., Sarira, T. V., Siman, K., & Koh, L. P. (2021). Global potential and limits of mangrove blue carbon for climate change mitigation. Current Biology, 31(8), 1737-1743.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.01.070

Copyright (c) 2025 Jurnal Wasian

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Copyright and License

All articles published in Wasian Journal are the property of the authors. By submitting an article to Wasian Journal, authors agree to the following terms:

-

Copyright Ownership: The author(s) retain copyright and full publishing rights without restrictions. Authors grant the journal the right to publish the work first and to distribute it as open access under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

-

Licensing: Articles published in Wasian Journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). This license allows others to share, copy, and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and adapt, remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided that proper credit is given to the original author(s) and the source of the material

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. -

Author's Rights: Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges and greater citation of published work.

-

Third-Party Content: If your article contains material (e.g., images, tables, or figures) for which you do not hold copyright, you must obtain permission from the copyright holder to use the material in your article. This permission must include the right for you to grant the journal the rights described above.

-

Reprints and Distribution: Authors have the right to distribute the final published version of their work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), provided that the original publication in Wasian Journal is acknowledged.

For the reader you are free to:

- Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format for any purpose, even commercially.

- Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially.

- The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms.

Under the following terms:

- Attribution — You must give appropriate credit , provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made . You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

- No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

Notices:

You do not have to comply with the license for elements of the material in the public domain or where your use is permitted by an applicable exception or limitation .

No warranties are given. The license may not give you all of the permissions necessary for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy, or moral rightsmay limit how you use the material.