Insectivorous Birds Dominate Across Land-Use Gradient Revealing Unexpected Ecological Resilience in Tropical Forest-Coffee Landscapes

Abstract

Vegetation is essential for birds to fulfil their life requirements. Monoculture coffee plantations, coffee-based agroforestry systems, and forests in HKm Wana Jaya provide potential habitats for various animal species, including birds. This research assessed bird diversity, richness, evenness, species dominance, feeding guilds, and conservation status across these three land cover types. The point count method was employed for data collection. Data were quantitatively analysed using the Shannon-Wiener diversity index, the Margalef richness index, the Pielou evenness index, and the Simpson dominance index. The study recorded 35 bird species from 19 families comprising 167 individuals. Species diversity values across all three land cover types fell within the moderate category, with forest exhibiting the highest value (2.988), followed by coffee agroforestry (2.648) and monoculture coffee (2.035). The highest species richness was found in the forest (5.429) and the lowest in monoculture coffee (2.970). The highest species evenness was recorded in coffee agroforestry (0.935) and the lowest in monoculture coffee (0.849), while species dominance values across all three land cover types were categorised as low (0.061-0.172). Insectivorous birds dominated feeding guilds across all habitat types, revealing unexpected ecological resilience. Of the species recorded, 29 are classified as Least Concern, two as Vulnerable, four as Near Threatened, while 10 species are protected under national legislation, and three species are listed in CITES Appendix II. The findings suggest that while forests maintain the highest biodiversity value, coffee agroforestry systems can provide crucial supplementary bird conservation habitats in modified landscapes.

1. Introduction

Birds are among the most recognizable organisms on Earth (Ghifari et al., 2016). They play direct ecological roles in agriculture through pest control, pollination of plants, and natural seed dispersal (Nurdin et al., 2018). Indirectly, birds often serve as bioindicators of environmental quality, helping determine the level of degradation and quality of surrounding ecosystems (Ridwan, 2015; Saputra et al., 2020). Birds are widely utilized by humans as pets, food sources, economic resources, and for aesthetic purposes (Adelina et al., 2016). They can be found in almost all types of environments, from polar regions to deserts, from coniferous forests to tropical rainforests, and from rivers and wetlands to oceans (Darwis et al., 2020).

Birds have the remarkable ability to inhabit nearly all habitat types, displaying high mobility and excellent adaptation to diverse environments (Welty 1982; Rohiyan et al., 2014). They represent one of Indonesia's most significant biodiversity resources due to their widespread distribution (Raungku et al., 2018). As of 2024, Indonesia is home to 1,836 bird species, a number that has increased significantly over the past decade. Of these, 558 species are protected, 542 are endemic, 470 have restricted distributions, 32 are critically endangered, 51 are endangered, 83 are vulnerable, 220 are threatened with extinction, 1,435 are at low risk, and data are insufficient for 7 species (Junaid and Jihad, 2024).

Each bird species has unique habitat requirements; an environment preferred by one species may be unsuitable for another (Sujatnika et al., 1995; Paramita et al., 2015). Habitat selection by birds is based on their daily activities, including resting, mating, feeding, perching, sheltering, and nesting (Rumanasari et al., 2017). Factors influencing bird diversity include habitat diversity, which functions in providing food, water, rest, and breeding areas (Alikodra, 2002; Hadinoto and Suhesti, 2021). Another factor enhancing bird diversity is the availability of diverse tree species (Saefullah et al., 2015). Greater diversity in plant species and vegetation structure typically corresponds with increased bird diversity (Fikriyanti et al., 2018).

The protected area of KPH Batutegi, which serves as bird habitat, has experienced ongoing deforestation. Research by Gymnastiar (2024) revealed that forest cover in KPH Batutegi decreased by 7,979.9 hectares between 2016 and 2022. During the same period, agroforestry land cover increased from 11,486.20 hectares in 2016 to 19,935.25 hectares in 2022, while monoculture areas expanded from 13,780.36 hectares to 16,935.25 hectares. This high rate of land cover change in KPH Batutegi is driven by significant human activity causing physical changes to vegetation cover. One of the strongest factors influencing bird presence and diversity is the variety and composition of vegetation in an area (Hardina et al., 2020). Bird diversity varies across different vegetation groupings (Ridwan, 2015).

Research conducted by Maulana et al. (2025) in natural forest cover of Gapoktan Sinar Harapan in the HKm area of KPH Batutegi showed a positive relationship between bird species diversity and tree species diversity, demonstrated by high species diversity values in that land cover (3.07). Therefore, this research is important to understand how physical vegetation changes affect bird presence across these three land cover types. This study aims to determine the family groups, diversity, richness, evenness, dominance of bird species across these three land cover types, feeding groups, and conservation status of birds. Based on these issues, this research is important to assess the current state of bird diversity, providing new information for consideration in developing bird conservation policies in protected forests.

2. Method

1) Research Area

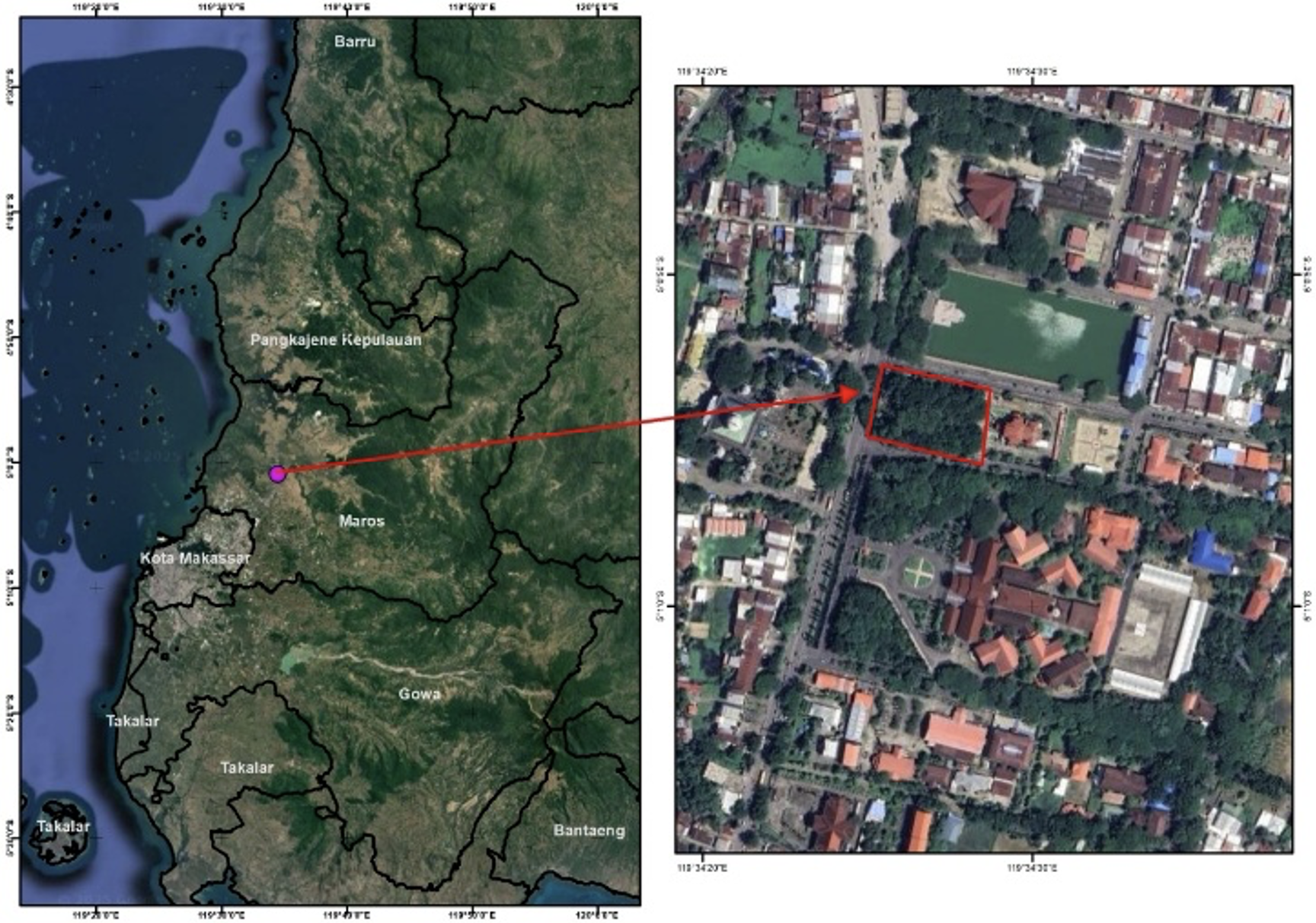

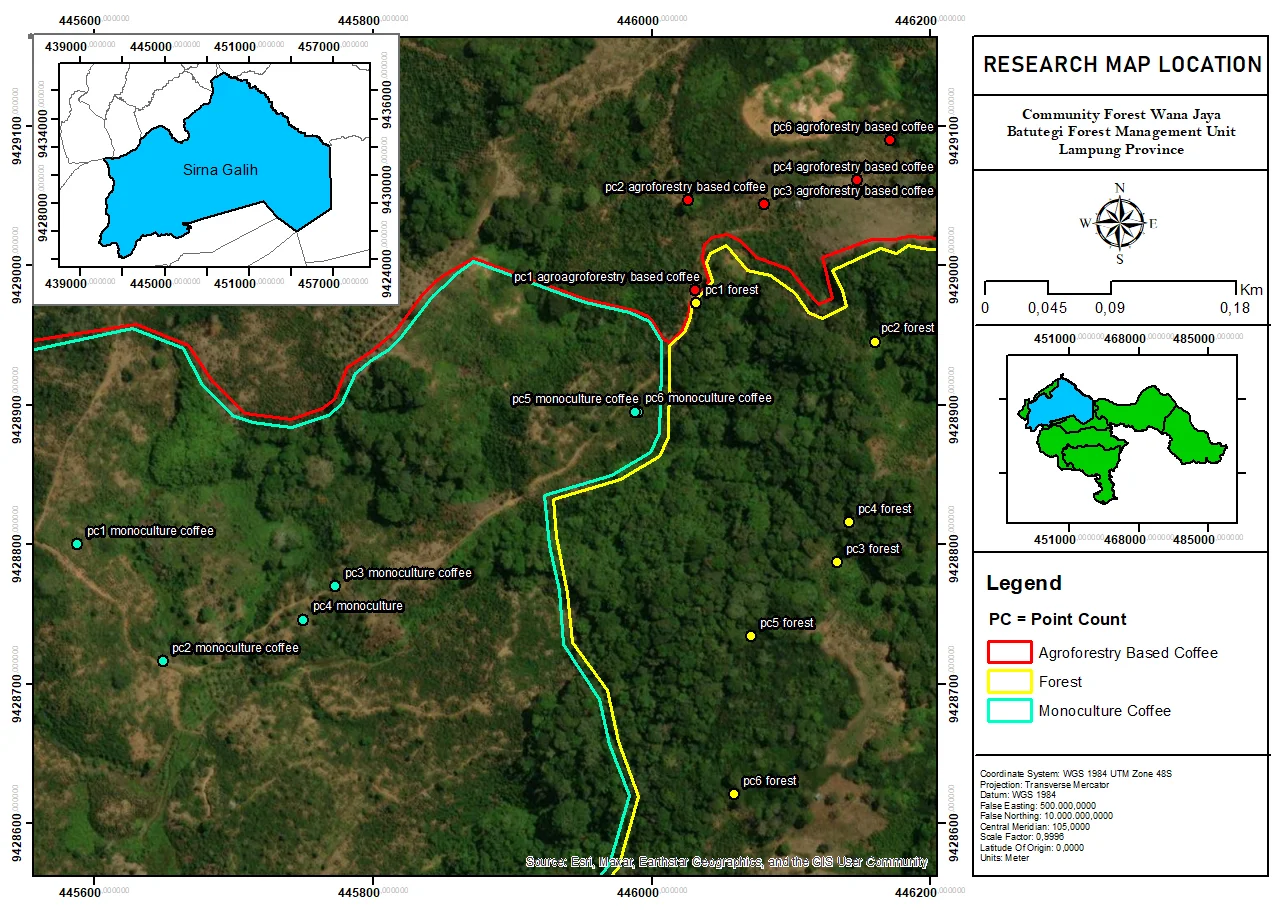

This research was conducted from October to November 2024 in monoculture coffee plantations, coffee-based agroforestry systems, and forests within the HKm managed by Gapoktan Wana Jaya. This HKm is located in the utilization block of KPH Batutegi. The area was selected due to its varied land cover types comprising forest, coffee agroforestry, and monoculture coffee. Geographically, the research site is located at coordinates 5°10'01.3"S 104°30'50.4"E. The land cover conditions exist within a single hilly landscape, with the hill position from top to bottom consisting of forest, coffee agroforestry, and monoculture coffee. Equipment used in this study included cameras, binoculars, watches, and writing instruments, while materials used were tally sheets, a field guide for bird species identification titled based on MacKinnon et al. (2010); Taufiqurrahman et al. (2022). The Merlin Bird ID application, and the e-bird website (https://ebird.org/home).

Figure 1. Research Location Map

2) Data Collection Method

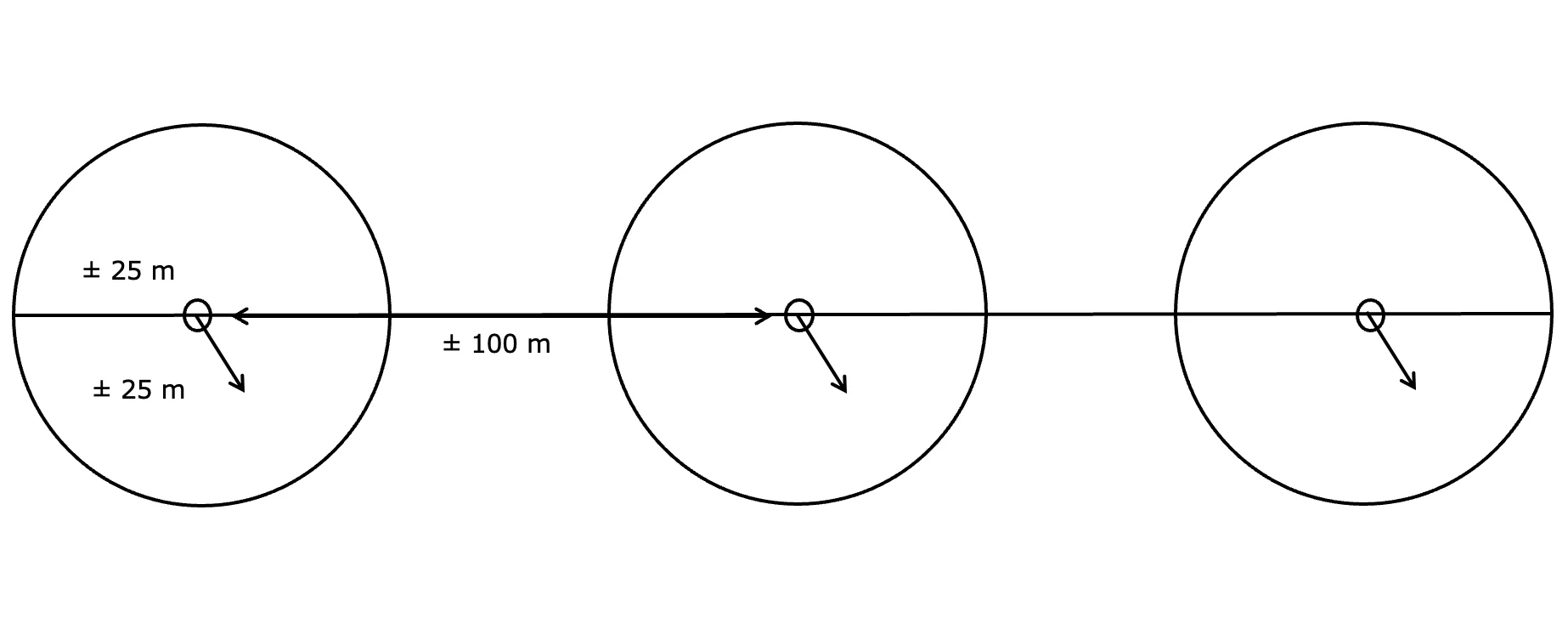

Field data collection employed the point count method. This method was chosen considering vegetation conditions and tracking path conditions to increase the likelihood of bird encounters. In areas with closed vegetation such as forests, uneven topography, and other geographic conditions that make it impossible to create straight transect lines, the point count method is preferred (Irham et al., 2018). The point count method can also be used across various seasons, climates, and habitats, and has been frequently used in tropical regions including Indonesia, as well as in regions with four seasons (Hutto et al., 1986; Kurniawan and Arifianto, 2017).

Figure 2. Point count illustration

Data collection was conducted by remaining stationary at a counting point and recording encountered birds within a specific time period (Fayogi et al., 2019), with 10 minutes allocated for each observation point (Fayogi et al., 2019). Data collection used 6 counting points in each land cover type, with 6 repetitions to avoid data bias (Sabaruddin et al., 2017). The distance between counting points was approximately 100 meters from the center of one point count to the center of the next, with an observation radius of approximately 50 meters (Al-mubarok, 2013). The distance between observation points of approximately 100 meters was maintained to avoid recording the same bird species (biased data). The observation radius used was appropriate for each type of land cover; in this case, the forest cover in HKm Wana Jaya was not dense due to tree tapping activities and land clearing for monoculture coffee. Bird data collection was conducted during birds' active periods: in the morning from 06:00 to 09:00 WIB and in the afternoon from 15:00 to 18:00 WIB (Iswandaru et al., 2020). Data collected in this study included the number of bird species and the number of individuals.

3) Data Analysis

The collected data were subsequently analyzed quantitatively using the Shannon-Wiener species diversity index, Margalef species richness index, Pielou species evenness index, and Simpson species dominance index. Additionally, other data were analyzed descriptively to categorize species based on family groups, feeding groups, and bird conservation status.

Shannon-Wiener Index

H' = - ∑ Pi Ln (Pi)

Where:

H' = Shannon-Wiener index value

Pi = ni/N

Ni = total number of individuals of species i

N = overall total, and

Ln = natural logarithm

Diversity criteria (Odum, 1971; Saputri et al., 2022):

H' < 1: low diversity

1 < H' ≤ 3: moderate diversity

H' > 3: high diversity

Margalef Richness Index

D = S-1/Ln(N)

Where:

R = Margalef species richness index

S = number of species

N = number of individuals

ln = natural logarithm

Richness criteria (Jorgensen et al., 2005; Ekowati et al., 2016):

D < 2.5: low richness

2.5 < D < 4: moderate richness

D > 4: high richness

Pielou Evenness Index

E = H'/Ln (S)

Where:

E = Pielou evenness index

H' = Shannon-Wiener diversity index

S = number of species

ln = natural logarithm

Evenness criteria (Daget, 1976; Saputri et al., 2022):

0 < E ≤ 0.50: stressed community

0.50 < E ≤ 0.75: unstable community

0.75 < E ≤ 1: stable community

Simpson Dominance Index

C = ∑ (ni/N)²

Where:

C = dominance index

Ni = number of individuals of each species

N = total number of individuals of all species

Dominance criteria (Fikriyanti et al., 2018):

0 < C ≤ 0.5: low dominance

0.5 < C ≤ 0.75: moderate dominance

0.75 < C ≤ 1: high dominance

Feeding groups

Birds found in monoculture coffee plantations, coffee-based agroforestry, and forests were categorized based on their feeding groups. Bird feeding groups referred to the research by Rumblat (2016), specifically: insectivores, carnivores, granivores, frugivores, and nectarivores.

Bird conservation status

Bird conservation status was determined based on 1 national criterion and 2 international criteria. National conservation status was based on the Regulation of the Minister of Environment and Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia No. P.106/MENLHK/SETJEN/KUM.1/12/2018 regarding the second amendment to the Regulation of the Minister of Environment and Forestry No. P.20/MENLHK/SETJEN/KUM.1/6/2018 concerning protected plant and animal species. International conservation status based on trade regulations referred to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), and threat status referred to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN).

3. Result and Discussion

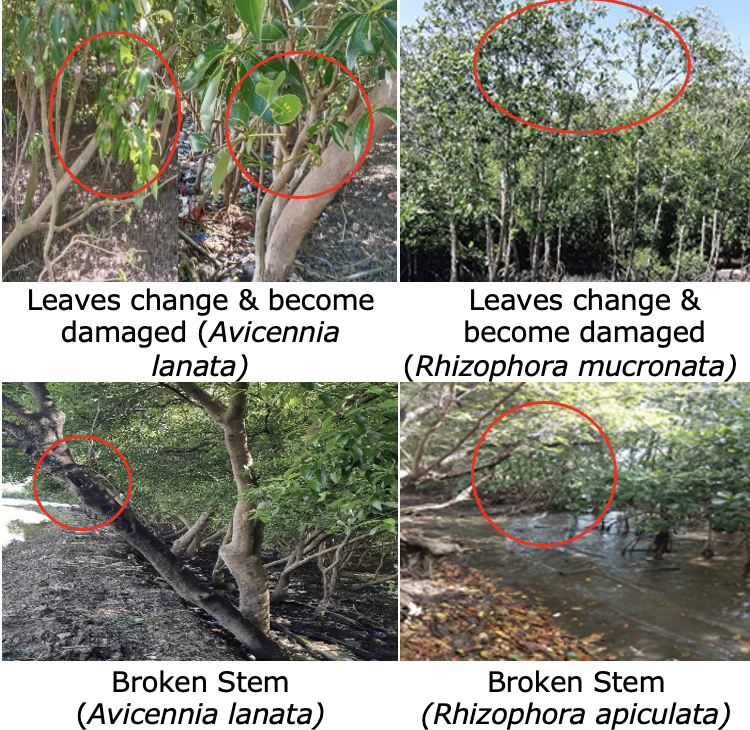

1) Bird species composition

A total of 35 bird species from 19 families comprising 167 individuals were recorded at HKm Wana Jaya (Table 1). These results demonstrate that each land cover type has different species, number of species, and families. Some bird species were found in only one land cover type, while others were distributed across all three land cover types. According to Celebes Bird Club (2006) and Sultika et al. (2017), bird distribution is influenced by chemical factors, habitat, and the presence or absence of other species inhabiting an area. Sulistyadi (2010) also mentioned that bird presence is influenced by the availability of plants used for food provision, nesting, and protection from predators.

Table 1. Bird species in monoculture coffee, coffee-based agroforestry, and forest land cover types

Note: Monoculture Coffee (MC), Agroforestry Coffee (AC), Forest (FF), migrated bird (*)

Among the three land cover types in the Gapoktan Wanajaya management area, forest had the highest number of bird species (26 species), while monoculture coffee had the lowest (11 species). The percentage of migratory and non-migratory birds in forest habitats was 9% and 91%, respectively. Three migratory bird species were found in the forest: Turdus obscurus, Eumyias thalassinus, and Muscicapa dauurica. Turdus obscurus breeds in northern Asia and migrates to the Philippines, Sulawesi, and Greater Sunda during winter, typically at elevations of 1,000-2,000 meters above sea level (MacKinnon et al., 2010). This is consistent with the location where these migratory birds were found—in forest land cover at elevations of 1078.80-1090.40 meters above sea level. Moreover, the observation period fell within the bird migration months (October-March). The abundance of bird species found in forests is attributed to birds' ability to adapt to their environmental conditions (Priyanto Saibi et al., 2021) and to forests providing facilities for birds as places to rest, nest, breed, and forage (Asep, 2011). The low presence of birds in monoculture coffee land cover is caused by homogeneous vegetation cover (Kamal et al., 2015), which does not provide suitable food for birds. Eight bird species were found across all three land cover types: Dicaeum trigonostigma, Pycnonotus aurigaster, Pycnonotus melanicterus, Collocalia esculenta, Microhierax fringillarius, Dicaeum trochileum, Dicaeum cruentatum, and Spilornis cheela.

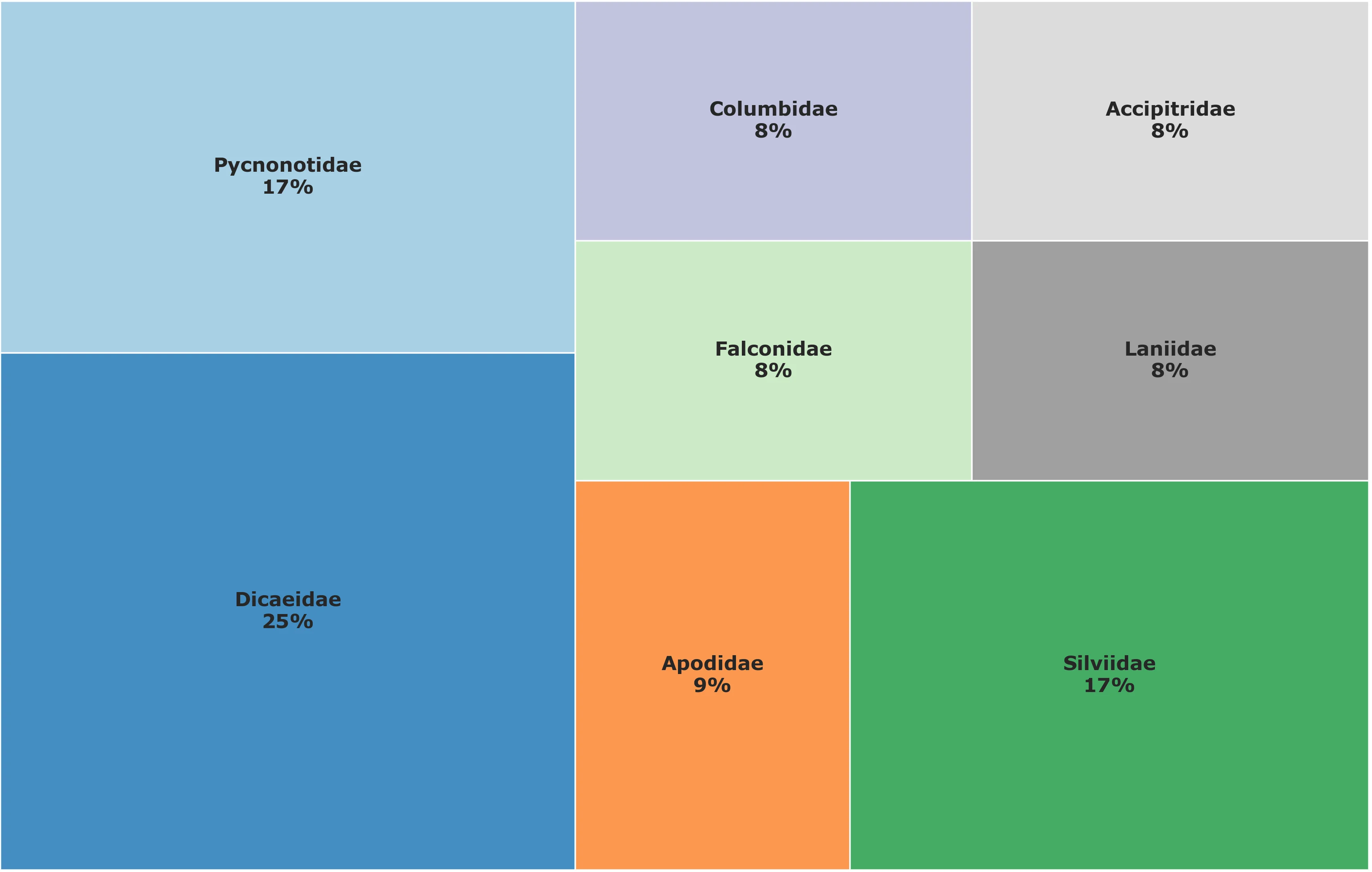

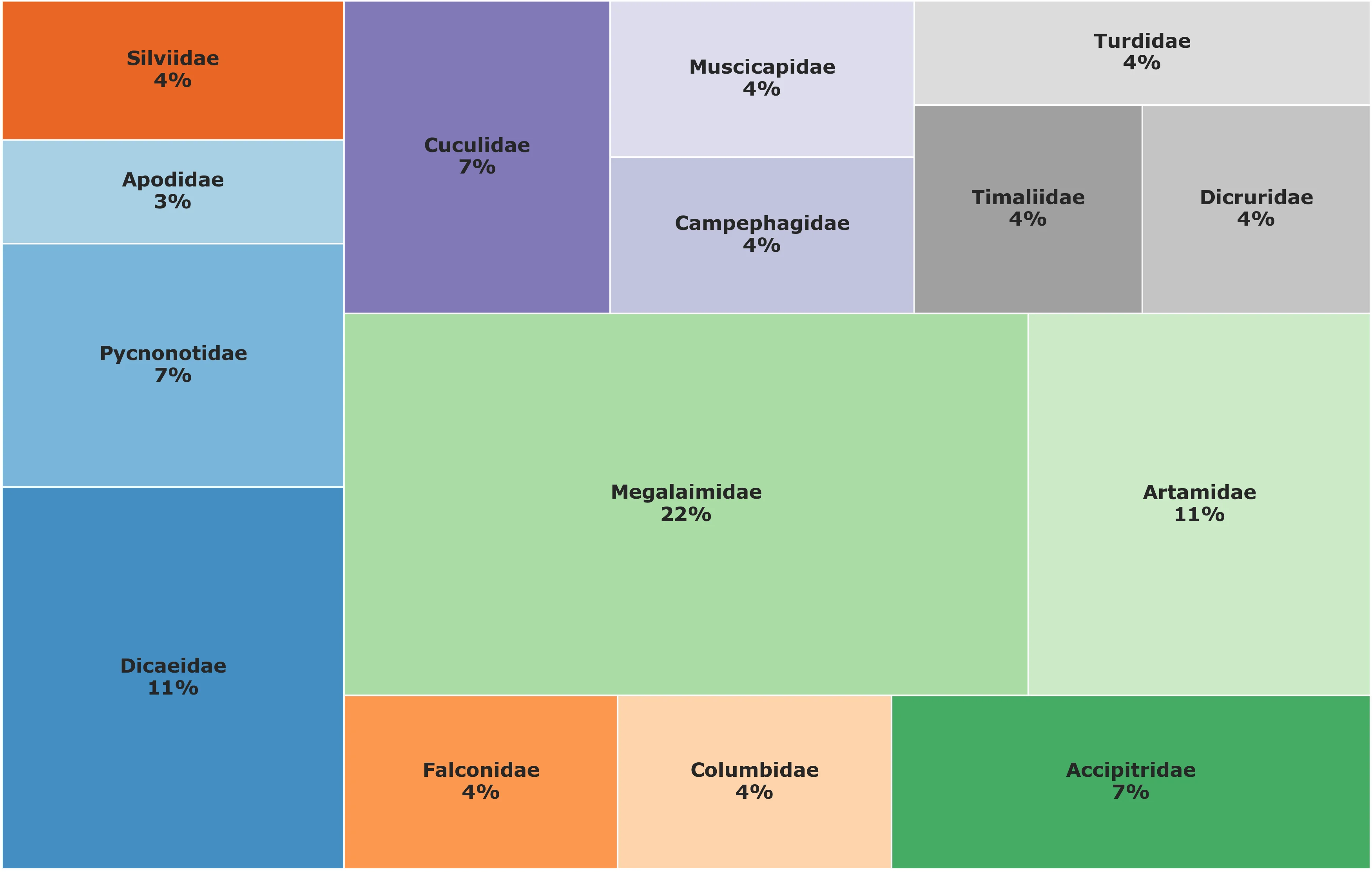

Figure 3. Percentage of bird families in monoculture coffee

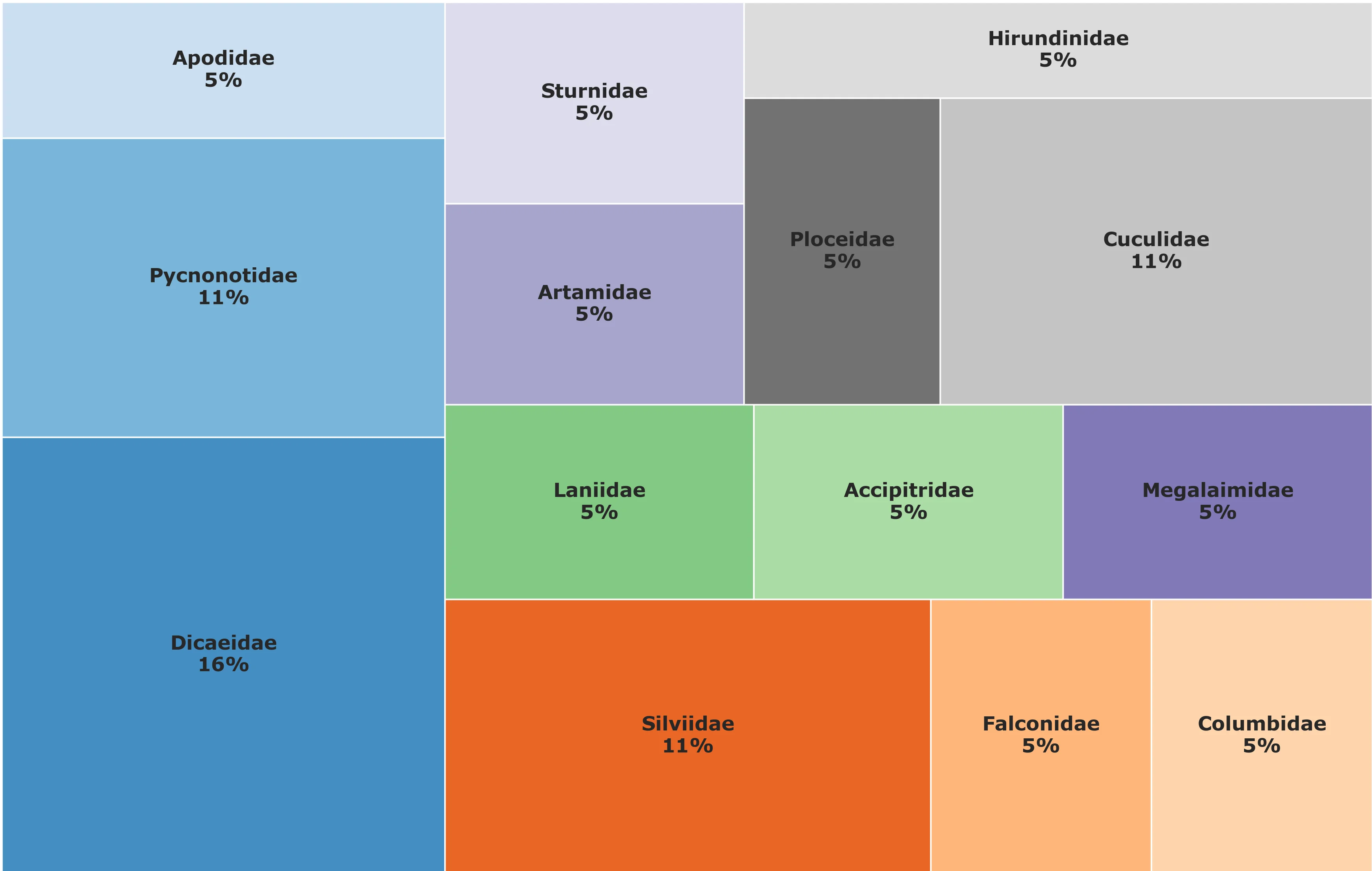

The Dicaeidae family had the highest percentage in monoculture coffee (25%) and coffee agroforestry (16%). Birds from this family are often found around plants infested with mistletoe, feeding on its fruits. Additionally, birds from the Dicaeidae family are commonly found in monoculture coffee because they prefer garden or field habitats, even yards (Kamal et al., 2015). The Megalaimidae family dominated forest habitats with a percentage of 22%. Birds from the Megalaimidae family, or barbets, feed on fruits, seeds, and flowers (MacKinnon et al., 2010). Six species from the Megalaimidae family were found in forests with high encounter rates, attributed to the availability of food from plants of the Moraceae family or fig family. Sihotang et al. (2013) stated that fruits from fig trees are the primary preferred food of barbet birds.

Figure 4. Percentage of bird families in coffee-based agroforestry

The bird most commonly found across all three land cover types was the Pycnonotus aurigaster. The Pycnonotus aurigaster is a species from the Pycnonotidae family (fruit and insect eaters) (Surya et al., 2013). This bird species has high adaptability and can be found in almost all land cover types, including shrubs, open trees, forest edges, yards, gardens, and urban parks (Zuhra and Kamal, 2022), as well as in monoculture coffee, coffee agroforestry, and forests. This bird species is also known to have a high tolerance for human presence and disturbances related to land cover changes (Erniwati et al., 2016). One bird species found in only one type of land cover—forest—was the Pericrocotus flammeus (Table 1). This is because Pericrocotus flammeus prefer primary forests and hop among tree canopies (Mackinnon et al., 2010). This bird was encountered only once during six field repetitions, at an observation site elevation of 1090.40 meters above sea level.

Figure 5. Percentage of bird families in forest

Figure 6. Ficus heteropleura in forest

All three land cover types at HKm Wana Jaya exhibited moderate diversity index (H') values (Table 2). The highest diversity index (2.988) was found in forest land cover, a condition attributed to forests having heterogeneous communities, meaning they contain various plant species and strata. The lowest diversity index was in monoculture coffee land cover (2.035), caused by the homogeneous vegetation structure of monoculture coffee plantations, which consists of only one plant species, thus affecting bird diversity (Fikriyanti et al., 2018). The most significant factor influencing bird diversity in a land cover type is the condition of vegetation structure, vegetation variation, and area size (Fadrikal, 2015), such that more varied vegetation corresponds with greater bird diversity (Asrianny et al., 2018).

Diversity is a unique characteristic of communities associated with the number of species, species richness, and species abundance as community components within an ecosystem (Ekowati et al., 2016). Species richness itself is defined as the number of species found in a place (Pratama et al., 2023). The richness levels from highest to lowest across the three land cover types were forest, coffee agroforestry, and monoculture coffee (Table 2). The varying levels of species richness across these three land cover types can be influenced by several factors. Factors supporting species richness in an ecosystem include food source conditions, inter-species competition, predation, and threats or disturbances to species within it (Kamaluddin et al., 2019). The low richness of bird species in monoculture coffee land cover is caused by several factors, including high human or farmer activity (Mubarik et al., 2020) in these areas, especially during harvest season. Additionally, birds are characterized by being disturbed in their presence when land cover changes have occurred (Bohada-Murillo et al., 2020).

Table 2. Diversity, richness, evenness, and dominance of bird species in monoculture coffee, coffee-based agroforestry, and forest land cover types

Note: H’ (diversity), D (richness), E (evenness), dan C (dominance), MC (Monoculture Coffee), AC (Agroforestry Coffee), FF (Forest).

Species evenness (E) indicates species dominance within a community, while the dominance index value shows the pattern of species dominance over other species in the community (Mawazin and Subiakto, 2013; Ekowati et al., 2016). The evenness index values for coffee agroforestry and forest were not significantly different, ranging from 0.917 to 0.935 (approaching 1). An evenness index value below 0 indicates low evenness between species, while an E value approaching 1 shows relatively uniform distribution among species (Odum, 1971; Dillak et al., 2020). In this case, both land cover types exhibited relatively uniform bird species evenness.

The dominance index (C) values across all three land cover types ranged from 0.061 to 0.172, categorized as low (approaching 0). This means that none of the three land cover types were dominated by one or a few specific bird species (Pertiwi, 2021). Dominance of a species occurs when that species can adapt to its habitat. In this case, that species competes with other species for food and habitat space (Alikodra, 1989; Windharti et al., 2013).

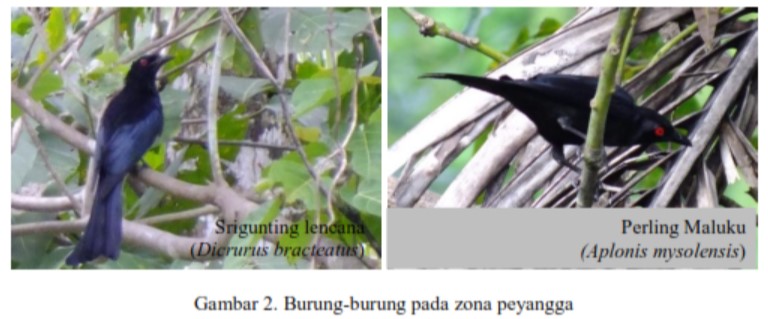

2) Feeding guilds analysis

Bird feeding gruilds across the three land cover types at HKm Wana Jaya were relatively varied, consisting of four feeding groups: frugivores (fruit eaters), granivores (seed eaters), insectivores (insect eaters), and carnivores (meat eaters, including small vertebrates, small invertebrates, and small mammals). The insectivorous group was divided into four types based on hunting methods (Rumblat et al., 2016): insect-eating birds, insect-snatching predators from the Falconidae family, aerial insect hunters from the Artamidae family, and branch-perching insect hunters from the Dicruridae family.

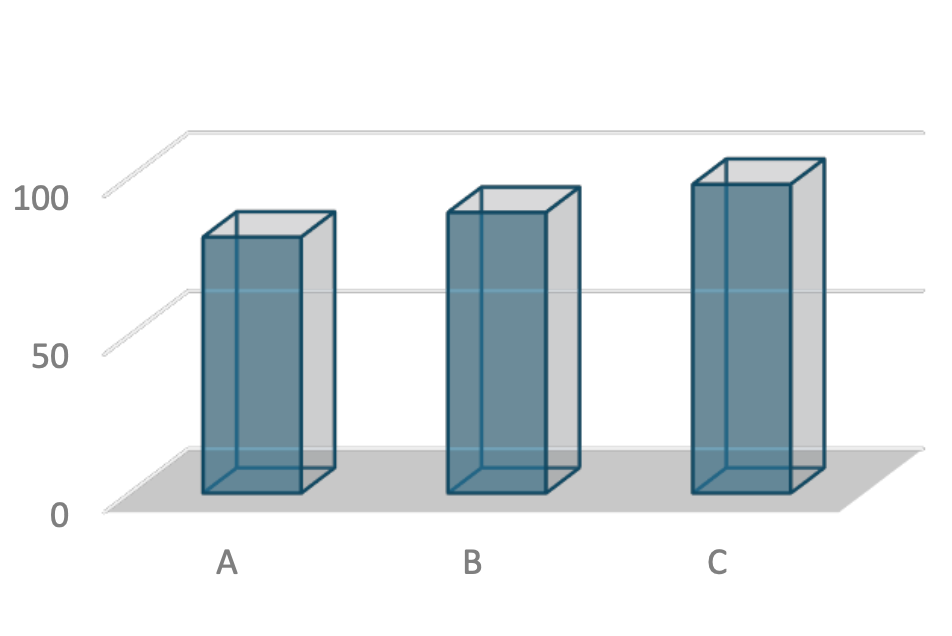

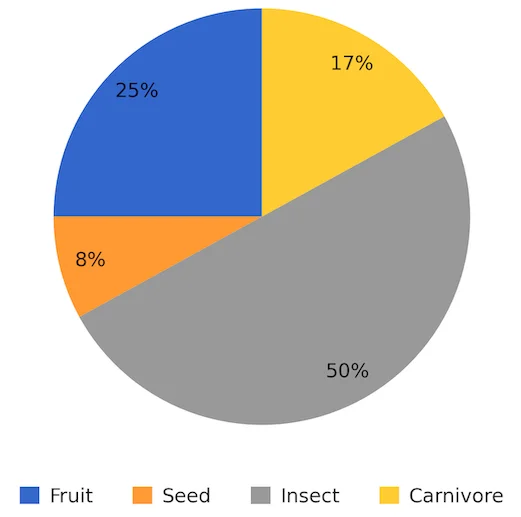

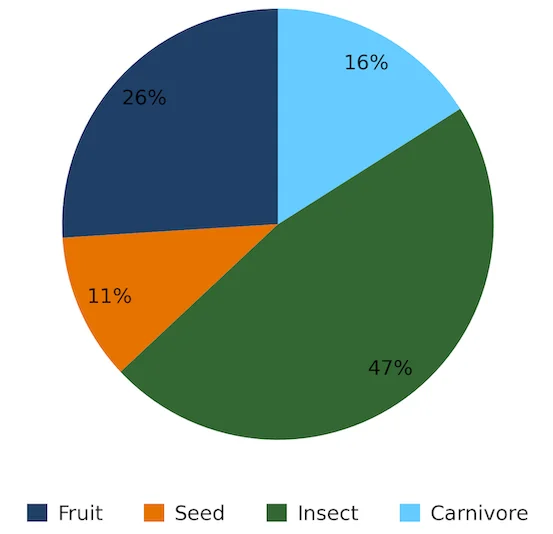

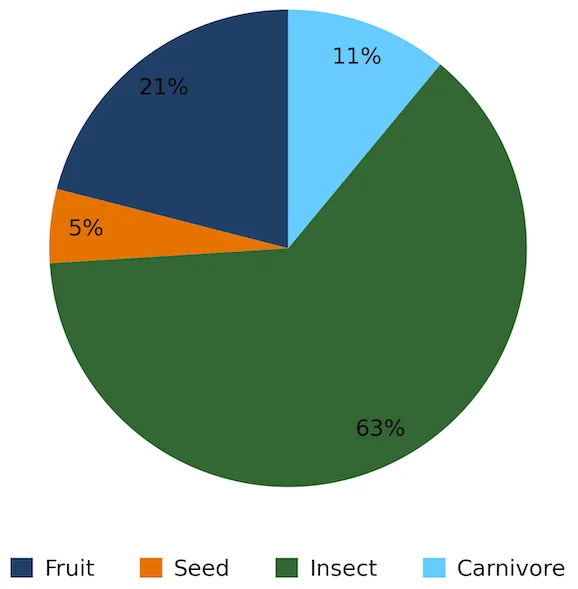

The number of birds in each feeding group varied, with differences influenced by available food quantities. This indicates that each feeding group has its own way of responding to environmental conditions (Rofiq et al., 2021). Insectivores dominated all three land cover types: monoculture coffee (50%), coffee agroforestry (47%), and forest (63%). The abundance of insectivorous bird species across all three land cover types is caused by deteriorating land cover, indicated by tree tapping activities and the felling of large trees, inadequate implementation of shade tree planting in coffee agroforestry, and increased monoculture plantations. These issues impact insect population increases (Loskova et al., 2013; Iswandaru et al., 2022) and reduced vegetation variety. Besides the dominance of insectivorous birds, frugivores also had the second-highest percentage across all three land cover types: coffee agroforestry (26%), monoculture coffee (25%), and forest (21%). This is due to the presence of avocado plants, bananas, guava, papaya in coffee agroforestry, mistletoe plants bearing fruit in monoculture coffee, and fig fruits in forests. Plants that produce fruits such as those in forests, coffee agroforestry, and monoculture coffee are utilized not only by frugivorous birds but also by insectivorous birds (Surya et al., 2013).

Figure 7. Percentage of feeding groups in monoculture coffee

Figure 8. Percentage of feeding groups in coffee-based agroforestry

Figure 9. Percentage of feeding guilds in forest

3) Conservation status

The conservation status of birds at HKm Wanajaya (Table 4) presents various protected and endangered bird species. Based on P.106/MENLHK/SETJEN/KUM.1/12/2018 concerning protected plant and animal species, 10 bird species (28.57%) found were protected, including the Fire-tufted Barbet, while the other 25 species (71.43%) were not protected. Additionally, the most common threat status was LC (82.86%), meaning these birds have a low risk or are not threatened with extinction. However, without protection efforts, there is potential for various bird species with LC status to increase their threat level.

Figure 10. Dead tree due to tapping

Figure 11. Forest condition becoming bare, dominated by coffee plants

Table 3. Conservation status of birds

Ryby-throated Bulbul and Javan Myna have Vulnerable (VU) status, indicating a high risk of extinction in the wild. Birds found with Near Threatened (NT) status included Red-throated Barbet, Black-bellied Malkoha, Raffles's Malkoha, and Brown Barbet. Based on their trade status, three bird species were categorized as Appendix II: Black-thighed Falconet, Crested Serpent Eagle, and Changeable Hawk-eagle. This means that these birds with this status will be threatened with extinction if traded without regulation.

Information obtained from farmers who assisted with data collection in the field explained that there were no illegal hunting activities at the location. This also explains why many protected bird species from the Megalaimidae family were still found in the forest, with a total of 6 species. If hunting does not occur in the future, another factor for bird extinction at this location is the conversion of forest land to non-forest uses (Riniarti and Setiawan, 2014). Field conditions showed that there were dead forest trees due to tapping, and coffee was beginning to be planted beneath these dead trees. Additionally, land with steep slopes (40°-45°) was largely planted with coffee, causing hills to become dominated by coffee plants and open areas.

Figure 12. Black-browed Barbet (Psilopogon oorti)

Figure 13. Eyebrowed Thrush (Turdus obscurus)

4. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that land-use changes from forest to coffee cultivation systems have significant implications for avian community structure in the HKm Wana Jaya region. A total of 35 bird species from 19 families comprising 167 individuals were recorded across the three land cover types. Our findings reveal a clear diversity gradient, with highest bird diversity in forest habitats (H' = 2.988), followed by coffee agroforestry (H' = 2.648), and lowest in monoculture coffee plantations (H' = 2.035). Similarly, species richness showed the same pattern, with highest values in forest (D = 5.429) and lowest in monoculture coffee (D = 2.970).

The dominance of insectivorous birds across all land cover types—comprising 63% of forest bird communities, 47% of coffee agroforestry, and 50% of monoculture coffee systems—represents a particularly noteworthy finding. Contrary to conventional expectations that modified habitats would show significant shifts in trophic structure, the consistent dominance of insectivorous birds across the disturbance gradient reveals unexpected ecological resilience in these communities. This trophic structure maintenance suggests that even as landscapes transition from forests to agricultural systems, certain ecological functions may demonstrate resilience, potentially supporting both conservation and sustainable agricultural production objectives through natural pest control services.

The presence of three migratory species exclusively in forest habitats underscores the irreplaceable ecological value of remnant forest patches. Additionally, the conservation significance of these landscapes is highlighted by the presence of globally threatened species, including two Vulnerable and four Near Threatened species according to IUCN criteria, as well as ten nationally protected species.

While our results confirm that forest habitats support the highest bird diversity, the relatively high diversity maintained in coffee agroforestry systems suggests that these modified landscapes, when properly managed, can serve as valuable complementary habitats for bird conservation. These findings have important implications for landscape-level conservation planning in regions experiencing forest conversion to agricultural uses. We recommend implementing policies that maintain forest fragments, promote coffee agroforestry over monoculture systems, and establish connectivity corridors between natural and modified habitats to maximize biodiversity conservation in this rapidly changing tropical landscape.

5. Author Contributions

LP and DI include writing, field data collection, designing analysis, performing analysis, and interpreting results. YRF contribution includes designing analysis and performing analysis. AD contribution includes collecting data, designing analysis, and performing analysis. The contributions HK, CW, RS, SH, N and IGF include designing analysis.

6. Competing Interests

We guarantee that the journal is the original work of the author. We guarantee that the journal has not been published before and is not being considered for publication elsewhere. On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author will be responsible for the submission of the journal manuscript. This statement states that the author has seen and approved the submitted journal manuscript. We declare that all authors listed on the title page have made significant contributions to this work and agree to submit it to Jurnal Wasian.

7. Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to PT. NESTLE Indonesia and the Department of Forestry, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Lampung, who funded this research through the 2021-2025 Research Collaboration scheme "Monitoring of Land and Biodiversity in the Watershed Rehabilitation Program." We also express our gratitude to KPH Batutegi for supporting this research.

8. References

Al-mubarok, F., & Wanagama, I. (2013). Pengaruh Strata Vertikal Dan Struktur. 1–8.

Daget, J. (1976). Les modèles mathématiques en écologie. Masson, Paris. 172 p. 90F.

Fikriyanti, M., Wulandari, W., Fauzi, I., & Rahmat, A. (2018). Keragaman Jenis Burung Pada Berbagai Komunitas di Pulau Sangiang, Provinsi Banten. Jurnal Biodjati, 3(2), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.15575/biodjati.v3i2.2360

Ghifari B, Hadi M, Tarwotjo U. (2016). Keanekaragaman dan kelimpahan jenis burung pada taman kota Semarang, Jawa Tengah. Jurnal Akademika Biologi 5 (4): 24-31

Kurniawan N, Arifianto A. (2017). Ornitologi: Sejarah, Biologi, dan Konservasi. UB Press. Malang

Welty JC. (1982). The Life of Bird. Saunders College Publishing. Phildelphia.

##submission.copyrightStatement##

##submission.license.cc.by4.footer##Copyright and License

All articles published in Wasian Journal are the property of the authors. By submitting an article to Wasian Journal, authors agree to the following terms:

-

Copyright Ownership: The author(s) retain copyright and full publishing rights without restrictions. Authors grant the journal the right to publish the work first and to distribute it as open access under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

-

Licensing: Articles published in Wasian Journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). This license allows others to share, copy, and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and adapt, remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided that proper credit is given to the original author(s) and the source of the material

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. -

Author's Rights: Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges and greater citation of published work.

-

Third-Party Content: If your article contains material (e.g., images, tables, or figures) for which you do not hold copyright, you must obtain permission from the copyright holder to use the material in your article. This permission must include the right for you to grant the journal the rights described above.

-

Reprints and Distribution: Authors have the right to distribute the final published version of their work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), provided that the original publication in Wasian Journal is acknowledged.

For the reader you are free to:

- Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format for any purpose, even commercially.

- Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially.

- The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms.

Under the following terms:

- Attribution — You must give appropriate credit , provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made . You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

- No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

Notices:

You do not have to comply with the license for elements of the material in the public domain or where your use is permitted by an applicable exception or limitation .

No warranties are given. The license may not give you all of the permissions necessary for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy, or moral rightsmay limit how you use the material.