Understanding Traditional Walnut Management System in Forest Communities of Selayar Islands, Indonesia

Abstract

This study examines traditional walnut management systems in Onto Village, Selayar Islands, Indonesia, using a Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) framework to understand how forest communities have developed and maintained sustainable resource management practices through generations. Through purposive sampling, 24 walnut farmers were interviewed to document indigenous management practices and utilization patterns associated with heritage trees averaging 40-50 years old. The research reveals a comprehensive five-stage management system—planting, harvesting, drying, peeling, and marketing—developed through accumulated traditional knowledge and continuously refined through practical application. Communities demonstrate sophisticated multi-functional utilization strategies that maximise resource efficiency: kernels serve as food and spices, timber provides construction materials, and shells become fuel for charcoal production. However, significant constraints limit the full potential of this traditional system, including reliance on conventional drying methods, limited processing technology, exclusive marketing of raw products, and absence of systematic replanting programmes, despite favourable market prices (IDR 60,000-100,000/kg). The study demonstrates how traditional ecological knowledge enables sustainable forest resource management whilst providing stable community livelihoods. The documented practices reflect generations of adaptive learning and environmental understanding that maintain both economic benefits and ecological integrity. However, finding highlights the complexities that arise between traditional knowledge and market pressures could emphasizing the importance of developing initiatives that honor traditional practices while also fostering positive economic outcomes. These insights unique contribute to understanding how traditional knowledge can inform sustainable forest management policies and support culturally appropriate development approaches in forest-dependent communities.

1. Introduction

In many developing nations, forest communities depend on non-timber forest products (NTFPs) not just for income but as a foundation for their way of life, offering sustainable alternatives that support both families and forest conservation. Unlike timber extraction, which requires tree felling and can lead to forest degradation, NTFP harvesting allows for sustainable resource utilization whilst maintaining forest ecosystem integrity (Chamberlain et al., 2019). The growing recognition of NTFPs' potential has positioned them as viable alternatives to conventional timber-based forest economies, offering pathways to biodiversity conservation, poverty alleviation, and community empowerment (Rini et al., 2024; Pattiwael et al., 2021). Beyond their economic value, NTFPs function as vital safety nets during times of hardship, provide essential nutrients for household health, and support the preservation of cultural heritage rooted in forest traditions (Amusa et al., 2024). The ongoing challenge lies in finding ways to use these resources sustainably—meeting current family needs without compromising future generations' access to the same benefits. This becomes particularly challenging when communities must navigate between their traditional practices and external pressures to modernize or meet changing market expectations (Ostrom, 2009; Scoones, 2009).

This study employs a Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) framework to examine walnut management practices in Onto Village. TEK provides a comprehensive analytical approach for understanding how indigenous communities develop, maintain, and transmit knowledge systems about sustainable resource management through generations of direct interaction with their environment (Berkes, 2012). This framework captures traditional knowledge that encompasses not only technical practices but also cultural values, management institutions, and adaptive strategies that enable communities to sustainably utilise forest resources whilst maintaining ecological integrity.

The TEK framework is particularly relevant for documenting and analyzing community-based forest management systems because it acknowledges the sophisticated understanding that local communities possess about resource ecology, seasonal patterns, harvesting techniques, and processing methods. Traditional ecological knowledge emerges from cumulative experience and is continuously tested and refined through practical application, resulting in management systems that are often well-adapted to local environmental conditions and community needs (Drew & Henne, 2006). By applying this framework, the study can systematically document the walnut management practices developed by the forest community, understand the knowledge transmission processes that maintain these practices across generations, and identify both the strengths and constraints within traditional management systems that inform sustainable forest resource utilization.

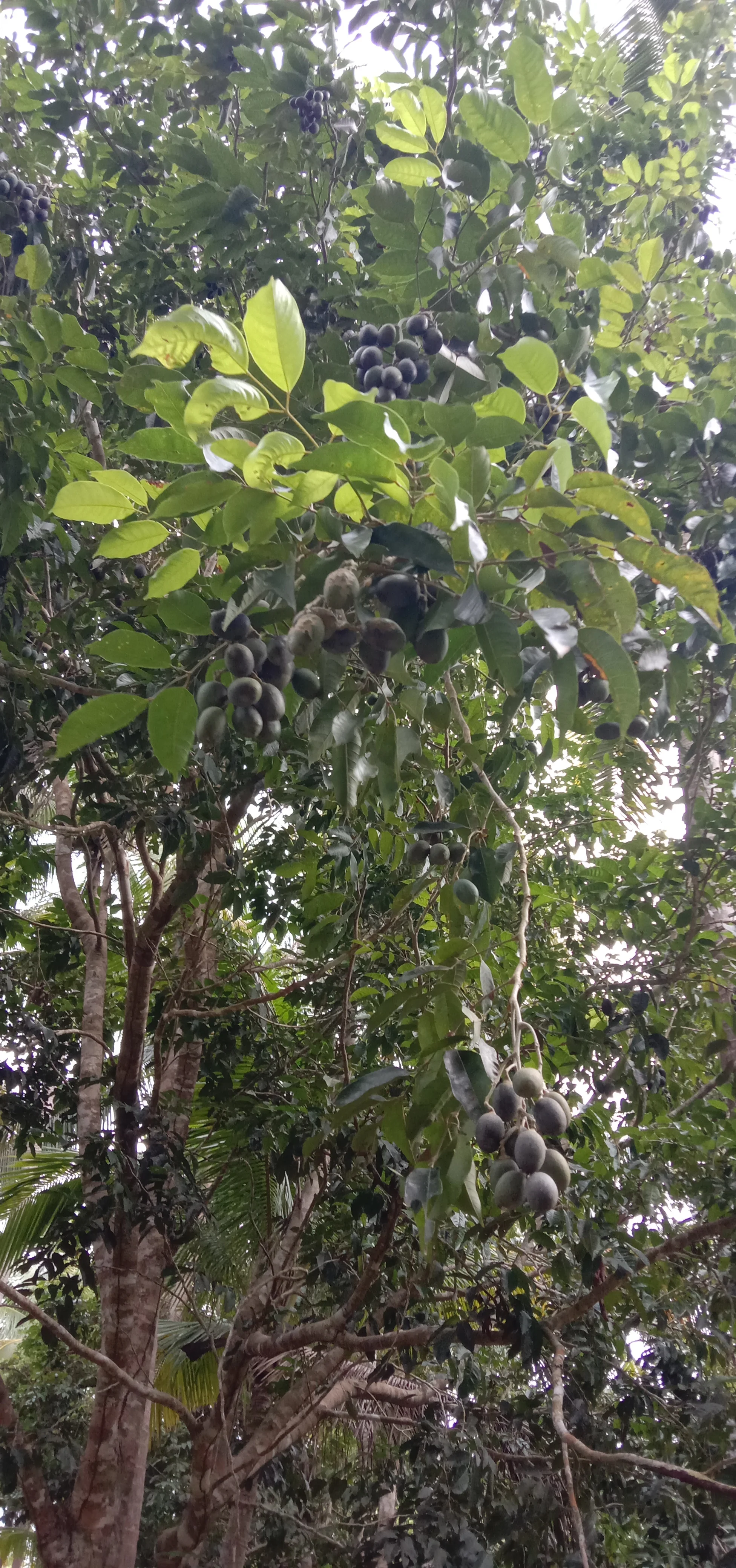

In Indonesia, particularly in eastern regions, indigenous walnut species such as Canarium indicum (kenari) are one of the most economically significant NTFPs, valued for their nutritional properties, medicinal applications, and industrial uses (Wen et al., 2023; Binici et al., 2021; Suryanto et al., 2021; Sundari et al., 2021; Mondo et al., 2024; Talib, 2022). Local communities have managed it for generations. Local communities have managed these resources for generations, developing sophisticated forest management strategies that integrate sustainable harvesting with long-term ecological foresight. However, since these practices are rarely documented in ways that policymakers recognize, they often get ignored in official forest management plans and miss out on potential improvements through appropriate technology.

Indonesia's vast forest resources support millions of forest-dependent people, yet NTFP management often remains marginalised in national forest policies prioritising timber production and conservation. This policy gap is particularly pronounced in remote island communities where traditional NTFP management systems operate with minimal external support or recognition. Without proper technical support, access to better processing equipment, or strong connections to markets, forest communities often struggle to earn decent incomes from their products, keeping families in poverty even when surrounded by valuable forest resources. Recent studies have highlighted the need for more nuanced approaches to NTFP development that respect traditional knowledge whilst introducing appropriate innovations (Makkarennu et al., 2023). However, few studies have comprehensively documented the complete management chain—from planting to marketing—in specific community contexts, limiting the evidence base for targeted interventions.

Onto Village in Bontomatene Sub-District, Selayar Islands Regency, presents a compelling case study for examining traditional walnut management systems. The village's 41 hectares of walnut cultivation contribute significantly to regional production (29.24 tonnes annually in Bontomatene District), positioning it as a key walnut-producing area in South Sulawesi (Plantation Agency, 2022). However, preliminary observations suggest that despite favourable market prices (IDR 60,000-100,000 per kilogram), local management practices remain largely traditional, potentially limiting both productivity and value-addition opportunities (Sulastina, 2024). The community's reliance on heritage trees (averaging 40-50 years old) without new plantings raises sustainability concerns, whilst the exclusive marketing of raw, unprocessed walnuts suggests missed opportunities for value addition. These conditions reflect broader challenges facing NTFP-dependent communities: how to maintain traditional knowledge systems whilst adapting to market opportunities and sustainability imperatives.

Despite the economic importance of walnuts in Selayar Islands and the evident reliance of Onto Village residents on walnut-based livelihoods, no comprehensive study has documented the complete management system employed by this community. This knowledge gap limits understanding of how traditional management practices align with principles of sustainable resource use, what specific constraints prevent communities from optimizing economic returns from walnut production, how traditional utilization patterns could be enhanced through appropriate technological or market interventions, and what lessons from this community's experience could inform NTFP development elsewhere in Indonesia. The absence of this documentation suggests that policymakers lack evidence-based insights for designing targeted support programmes or initiatives that respect traditional knowledge whilst enhancing community welfare and forest sustainability.

Thus, this study aims to capture and analyze the stages of traditional walnut management in Onto Village, to provide insights into how traditional NTFP management systems function in contemporary contexts. By examining the complete value chain from planting through marketing and documenting various traditional utilization patterns. This research seeks to identify the strengths of existing practices and enhancement opportunities to contribute on a global scale. This research has broader significance beyond the study site, providing guidance for support initiatives that value local ways of life whilst improving household incomes and promoting forest management that respects cultural practices.

2. Method

1) Research Location

This research was conducted in Onto Village, Bontomatene District, Selayar Islands Regency. This village has an area of 6.25 ha with a forest area of 473.25 m2. The location of Bontomatene District is at 120°26’40” - 120°32’ East Longitude and 5°45’ - 5°57’05” South Latitude. Onto Village has four hamlets, namely Maulana, Ontosapo, Sipatuo, and Sipatokkong hamlets. The administrative boundaries of Onto Village in Bontomatene District, Selayar Islands Regency are as follows: Batangmata Sapo Village borders to the north, Lalang Bata Village to the south, Maharayya Village to the west, and Balang Butung Village to the east.

Onto Village, Bontomatene District, Selayar Islands Regency has a climate with 946 mm of rainfall, 5 rainy months, an average daily temperature of 270 Celsius, and an altitude of 200-500 meters above sea level. The type of soil is clay with a slope of 250. Onto Village has a lowland, hilly, and mountain slope topography. The superior commodities of this village based on the area planted are coconut, walnut, and orange (Onto Village Profile, 2022).

The reason for choosing the research location was considered based on one of the centers of walnut business development on the island of Sulawesi which has reached the industrial market at the provincial level, namely located in Onto Village, Bontomatene District, Selayar Islands Regency with a land area of 41 hectares.

2) Type and Sources of Data

The data collected in this study consisted of primary data and secondary data. Primary data were obtained from direct interviews with respondents in this case walnut farmers and the results of field observations. The primary data collected included the form of walnut management consisting of planting, harvesting, drying, peeling, and marketing. In addition, data was also collected related to the use of walnuts by the community so far in Onto Village, Bontomatene District, Selayar Islands Regency. Secondary data were obtained through literature studies relevant to the research as well as data sourced from the Village, Sub-district, and agencies involved in the research. This includes physical conditions such as location, area, topography, soil, and climate.

3) Sampling Technique

The population in this study was the entire community in Onto Village, Bontomatene District, Selayar Islands Regency who manage walnut plants. Based on the initial survey, it was found that the population of walnut farmers in Onto Village was 33 people. Sampling was carried out using the Purposive Sampling technique. Purposive Sampling is sampling by setting specific criteria according to the research objectives. The criteria for the respondents selected were the community who manage walnuts (have walnut plants, collect, utilize, and market walnuts) which were considered relevant to the research objectives. The number of respondents selected was 24 walnut farmers based on the results of the sample calculation using the Slovin method. The Slovin method formula is as follows:

n = N / (1 + N x e²)

Note:

n = Number of samples

N = Number of population

e = Margin of error (10%)

4) Data Collection Techniques

Data collection techniques in this study were carried out in the following ways:

Field observation, which is a method carried out by collecting data through surveys or direct observation in the field.

Interviews, conducted by asking questions to respondents using the interview guide provided by providing some key questions to answer the research purpose, such as: (1) how is walnut management carried out by the community (planting, harvesting, drying, peeling, and marketing), (2) what are the benefits of walnuts? (3) How is the availability and use of technology in walnut management? (4) How is accessibility to walnut land? how much is the selling price of walnuts? (5) where does the community market the walnuts?

Literature study, A literature review was conducted to collect secondary data relevant to the study, such as data on the condition of the research location (geographical location, forest area, administrative boundaries, climate, rainfall, temperature, location altitude, soil type, regional superior commodities), land area, and walnut potential.

5) Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using a qualitative descriptive approach with Traditional Ecological Knowledge concepts guiding the interpretation of findings. Descriptive analysis examined the speech, writing, and behavior of respondents through narrative analysis via in-depth interviews to obtain data on walnut management practices and utilization patterns. The TEK perspective informed the analysis by recognizing management practices as expressions of traditional knowledge developed through generations of experience with forest resources. This strategy to ensure validity of research data was member checking by returning initial results to respondents for confirmation, ensuring that interpretations accurately reflected traditional practices and local understanding.

3. Result and Dicussion

1) Management of Walnut

The scope of walnut business management referred to in the study includes planting, harvesting, drying, peeling, and marketing. The following walnut management process can be seen in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Walnut management process

Planting

Walnut planting is actually no longer carried out by the community today because it has been done by their ancestors and then managed sustainably until now. On average, respondents have walnut plants with a managed tree age ranging from 40-50 years. Based on information from respondents, it was stated that walnut planting used to be done traditionally by selecting seeds that were considered suitable for planting which were marked by the size of the seeds, because if planting small and light seeds, the chances of them growing were very minimal. Walnut planting is widely carried out in remote areas because it is very suitable for growing in areas with cold weather. So far, the community has not cultivated walnut plants because according to information from respondents, they still have limited knowledge about walnut cultivation techniques or methods and the lack of support for cultivation technology is almost non-existent. This is in line with the statement (Iskandar, 2013) that communities around the forest who manage and utilize NTFPs need to get assistance from forestry extension workers to gain knowledge related to information technology in order to improve their welfare through forest resource management

Figure 2. Walnut plants that are still productive

Harvesting

If the planted walnuts have borne fruit and are blackish brown in color and have a hard texture, then it indicates that the walnuts are ready to be harvested / collected. Walnuts can be collected every day because walnut plants bear fruit all year round. The collection process is also quite easy because it can be done by waiting until the walnuts fall from the tree. Walnuts that have fallen should not be left on the ground for too long because the flesh of the fruit will be damaged, so walnut farmers usually collect them immediately. Walnut plants have a productive period of bearing fruit until the tree dies, so there is no specific limit. Farmers usually collect walnuts using buckets or sacks as containers. If the walnuts have been collected, farmers transport them to their homes using two-wheeled vehicles with an average distance to the forest area of around 10 km. The fairly long distance is an obstacle for walnut farmers in maximizing their harvest because the harvest that can be transported is still limited. Based on the statement (Wimolsakcharoen et al., 2020), the harvesting of NTFPs is actually easier than wood forest products because it is not necessary to cut down trees to harvest them, but rather in an easy, simple and environmentally friendly way, one of which is by collecting them when they have fallen from the tree.

Figure 3. Walnut harvest results

Drying

The harvest of walnuts that have been collected is then dried by drying them in the sun and can also be dried by smoking during the rainy season. Walnuts are usually dried in the sun for 3-5 days depending on the weather. Drying of walnuts is done before peeling in order to produce good quality peeled walnuts. The drying process carried out by the community so far is still very traditional because it is again and again constrained by modern drying tools or technology. Of course, the quality and quantity produced will be different when compared to modern and traditional use. Traditional tools are usually hampered by several obstacles, especially during the rainy season, so it is very important to minimize them by using more appropriate and adequate technology. The quality of walnuts produced from the drying process will greatly affect consumer buying interest and the selling price of the walnuts. So that support for drying technology such as drying ovens is needed by walnut farmers, especially the people of Onto Village, Bontomatene District, Selayar Islands Regency. Optimizing drying greatly affects the quality produced after drying in a commodity (Han et al., 2019). The manual walnut drying process under the sun can be seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Drying walnuts

Peeling

When

the walnuts are dry, the skin peeling process can be carried out to remove the

seeds using a simple cracking tool in the form of a machete and a stone as a

support. When cracked, usually some walnuts are broken and some are intact

depending on the drying process carried out. According to information from

respondents, intact walnuts indicate that the drying has been maximized, while

broken walnuts are caused by the drying process that has not been maximized or

due to unstable weather conditions during drying. Walnuts that have been

removed from their skins are then dried again before being marketed. The drying

process is the same before peeling by drying them in the sun. After the walnuts

are dry, the marketing process is carried out. Peeling the walnut skin needs to

be done carefully so that the fruit flesh is not destroyed and you can get

intact peeled walnuts to get a high selling price (Fordos et al., 2023).

Figure 5. Peeling

walnuts Marketing Farmers

have been selling peeled walnuts for Rp60,000/kg. Walnut farmers usually market

walnuts directly to consumers, and some market them to collectors. All

respondents interviewed marketed walnuts to collectors because according to

them the target market is clear and the income obtained is more and the demand

is unlimited because it depends on the amount to be sold or the production

results obtained. Meanwhile, if sold directly to consumers, the demand is

uncertain because it is adjusted to needs. Farmers also still sell walnuts in

raw form and have not been processed at all because of the limited appropriate

technology and the farmers' ability is still very minimal in terms of

processing. In fact, if processed into a product, it can provide added value to

increase income. Marketing of NTFPs is very important because in addition to

providing benefits for farmers and traders, it is also useful for meeting

consumer needs for NTFP commodities that are needed for daily needs or for

resale. Despite the promising production volume, the selling price is also

quite expensive so that businesses in the HHBK sector are highly recommended

while still paying attention to market opportunities, consumer demand, and the

right marketing strategies used for these commodities (Frey et al., 2023). Figure 6. Peeled

walnuts ready to be marketed Walnut

plants have many benefits in every part of them, from the trunk, fruit, to the

shell. Likewise, walnut is widely utilized by the community around the forest

in Onto Village, Bontomatene District, Selayar Islands Regency. The following

are the results of the analysis of the utilization of walnut presented in Table

1. The

results obtained regarding the use of walnuts by the Onto Village community are

in line with research conducted by Alim et al., (2023) in Talapaon Village,

West Makian District, South Halmahera Regency, North Maluku Province, which

stated that walnut plants have many benefits for the community who cultivate

and utilize them. Starting from the walnut flesh which is used as food

ingredients such as halua, macron, walnut bread, and cooking spices as a

flavoring. Similarly, in the Selayar Islands Regency, walnut stems are also

used by the people of Maluku Province as household building materials, such as

boards or furniture. Meanwhile, most walnut shells are thrown away and left

alone around the forest area. Only a few process it into compost to be used as

organic fertilizer. So when compared between the two locations of the walnut

center, basically the utilization is the same and both can generate economic

value if managed and utilized properly. However, to maximize its management and

utilization, there needs to be support in terms of mentoring or socialization

from forestry extension workers regarding the diversification of processed

walnut products so that they are not only marketed in the form of raw walnuts

as has been done by the people of Selayar Islands Regency so far. Table 1. Utilization of

walnut plants in Onto Village, Bontomatene District, Selayar Islands Regency This

study has revealing how forest communities have developed systematic approaches

to resource utilization through generations of experience. The comprehensive

five-stage management system—planting, harvesting, drying, peeling, and

marketing—demonstrates organised practices that have been maintained across

generations, with farmers managing heritage trees averaging 40-50 years old

without systematic replanting programmes. The

documentation reveals sophisticated resource utilization strategies where

communities employ virtually all parts of the walnut plant: kernels for food

and spices, timber for construction materials, and shells for fuel production.

However, the study identifies significant constraints that limit the economic

potential of these traditional practices, including reliance on

weather-dependent drying methods, limited access to processing technology,

exclusive marketing of raw products, and absence of new plantings despite

favourable market prices (IDR 60,000-100,000/kg). The relatively long transport

distances to forest areas (approximately 10km) further constrain harvest

optimization. These

findings have important implications for supporting traditional forest

management systems in Indonesia. Rather than replacing existing practices,

interventions should strengthen traditional approaches through complementary

support, including appropriate drying technologies for weather independence, processing

equipment to enable value addition, and technical assistance for systematic

replanting to ensure resource sustainability. Such support must recognize and

build upon the existing knowledge and practices that communities have developed

over decades of resource management. This

also contributes to comprehending how traditional management practices function

in contemporary contexts, demonstrating that community-based systems can

provide sustainable livelihoods whilst maintaining forest resources when appropriately

supported. Especially, for policymakers, this research highlights the

importance of documenting existing practices before designing interventions,

ensuring that support programmes build upon rather than replace community

knowledge and experience. Future

research should examine the effectiveness of technology-supported traditional

practices, explore systematic approaches to knowledge transfer between

generations, and investigate how traditional management systems can adapt to

changing market and environmental conditions whilst maintaining their core

sustainability principles. The

first author (RP) contributed to the writing, collected data, and designed the

analysis. The second (M) and third authors (R) contributed performed analysis,

interpreted the results, provided suggestions and comments during the writing

of the article The

authors declare that there is no conflict of interest throughout the entire

research process The

author would like to thank the people of Onto Village, Bontomatene District,

Selayar Islands Regency, for their assistance in providing field data related

to the research. Special thanks are extended to the Department of Agriculture

and Food Security of the Selayar Islands Regency, South Sulawesi Province,

Indonesia, for its support in collecting secondary data Iskandar, I.

(2013). Kajian sosiologis terhadap peran penyuluh kehutanan dalam pemberdayaan

masyarakat pada pengelolaan hasil hutan bukan kayu (HHBK) di Desa Tunggul Boyok

Kecamatan Bonti Kabupaten Sanggau. Jurnal Program Magister Ilmu Sosial

Universitas Tanjungpura, vol. 1, no. 0001

2) Utilization

of Walnut

4. Conclusion

5. Author

Contributions

6. Competing

Interests

7. Acknowledgements

8. References

الحقوق الفكرية (c) 2025 Jurnal Wasian

هذا العمل مرخص بموجب Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Copyright and License

All articles published in Wasian Journal are the property of the authors. By submitting an article to Wasian Journal, authors agree to the following terms:

-

Copyright Ownership: The author(s) retain copyright and full publishing rights without restrictions. Authors grant the journal the right to publish the work first and to distribute it as open access under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

-

Licensing: Articles published in Wasian Journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). This license allows others to share, copy, and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and adapt, remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided that proper credit is given to the original author(s) and the source of the material

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. -

Author's Rights: Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges and greater citation of published work.

-

Third-Party Content: If your article contains material (e.g., images, tables, or figures) for which you do not hold copyright, you must obtain permission from the copyright holder to use the material in your article. This permission must include the right for you to grant the journal the rights described above.

-

Reprints and Distribution: Authors have the right to distribute the final published version of their work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), provided that the original publication in Wasian Journal is acknowledged.

For the reader you are free to:

- Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format for any purpose, even commercially.

- Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially.

- The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms.

Under the following terms:

- Attribution — You must give appropriate credit , provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made . You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

- No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

Notices:

You do not have to comply with the license for elements of the material in the public domain or where your use is permitted by an applicable exception or limitation .

No warranties are given. The license may not give you all of the permissions necessary for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy, or moral rightsmay limit how you use the material.