Figure 1. Map of the Research Location

Accurate tree dimensional parameters, such as crown width, tree height, and diameter at breast height (DBH), are crucial for efficient forest planning, monitoring, and management (Saleh et al., 2023). According to Irundu et al. (2023), these measurements are essential for assessing important forest metrics like carbon stock, biomass, and timber volume. Manual field surveys remain the primary method of traditional data collection in Indonesia. Despite their general dependability, these approaches often require a substantial amount of time, money, and effort (Mohan et al., 2021). As a result, there is an urgent need for more economical and practical substitutes that can expedite the acquisition of tree dimension data, especially in expansive or isolated forest regions.

Recent years have witnessed a sharp increase in the use of remote sensing technology, especially Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), notably in the forestry industry. Because of their high-resolution, economical, and adaptable characteristics, UAVs present a possible substitute for gathering forest data (Guimarães et al., 2020). The assessment of forest volume, biomass, and carbon stock is only a few of the many forest inventory tasks that have made extensive use of these platforms. The majority of current applications, however, are still based on area-based techniques, which frequently fall short of individual tree-based methods in terms of precision (Dainelli et al., 2021; Guimarães et al., 2020; Schiefer et al., 2020). In response to this limitation, recent research has increasingly focused on developing tree inventory methods based on individual tree detection and segmentation from UAV-derived remote sensing data (Almeida et al., 2021; dos Santos et al., 2019; Mohan et al., 2021).

A variety of sensors and algorithms have been developed to support individual tree detection and segmentation using UAV-based remote sensing technologies (Dainelli et al., 2021; Diez et al., 2021; Hanapi et al., 2019). Commonly utilized sensors include RGB cameras, multispectral sensors, and Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) systems, as well as sensor combinations to enhance data quality and analysis outcomes (Dalponte & Coomes, 2016; González-Jaramillo et al., 2019). In parallel, the advancement of detection and segmentation algorithms has significantly improved the accuracy of tree inventory processes. These algorithms include more sophisticated machine learning and deep learning techniques as well as more conventional techniques like Object-Based Image Analysis (OBIA). Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) (Schiefer et al., 2020), Random Forests (Yang et al., 2022), and fully convolutional networks like U-Net are notable examples that have demonstrated good performance in defining individual tree crowns (Ball et al., 2023; Y. Li et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022).

Although numerous sensors and algorithms have been developed for individual tree detection and segmentation, several challenges remain. First, the use of advanced sensors such as multispectral and LiDAR systems involves high costs, limiting their accessibility for large-scale or resource-constrained applications (Sun et al., 2023). Second, selecting an appropriate algorithm that consistently achieves high accuracy across diverse forest conditions remains a complex issue (Irlan et al., 2020). Third, deep canopies and heterogeneous flora make it more difficult to apply individual tree segmentation techniques in forests with complicated structures, like Indonesia's natural forests (Nugroho et al., 2022). The development of more precise and economical techniques for individual tree segmentation is still urgently needed, especially in natural forest ecosystems, given the advantages and disadvantages of current methodologies (Zhang et al., 2024).

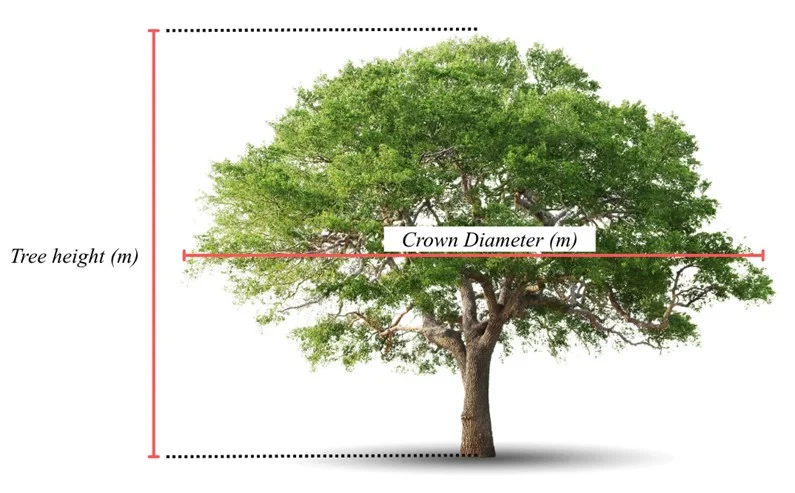

In this work, point clouds created from RGB photos of tropical natural forests were used to segment individual trees. RGB-derived point clouds provide a more affordable option for data collection when compared to other remote sensing technologies as LiDAR (Dell et al., 2019; Goldbergs et al., 2018). In addition, this study utilized a point cloud-based segmentation algorithm, which has demonstrated superior performance over raster-based or hybrid methods in previous research (Irlan et al., 2020). The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the accuracy of individual tree segmentation using RGB-based point clouds in structurally complex tropical forest environments. The findings are expected to support forestry stakeholders in selecting more efficient and accurate methods for acquiring tree dimension data, thereby facilitating improved forest management and monitoring practices.

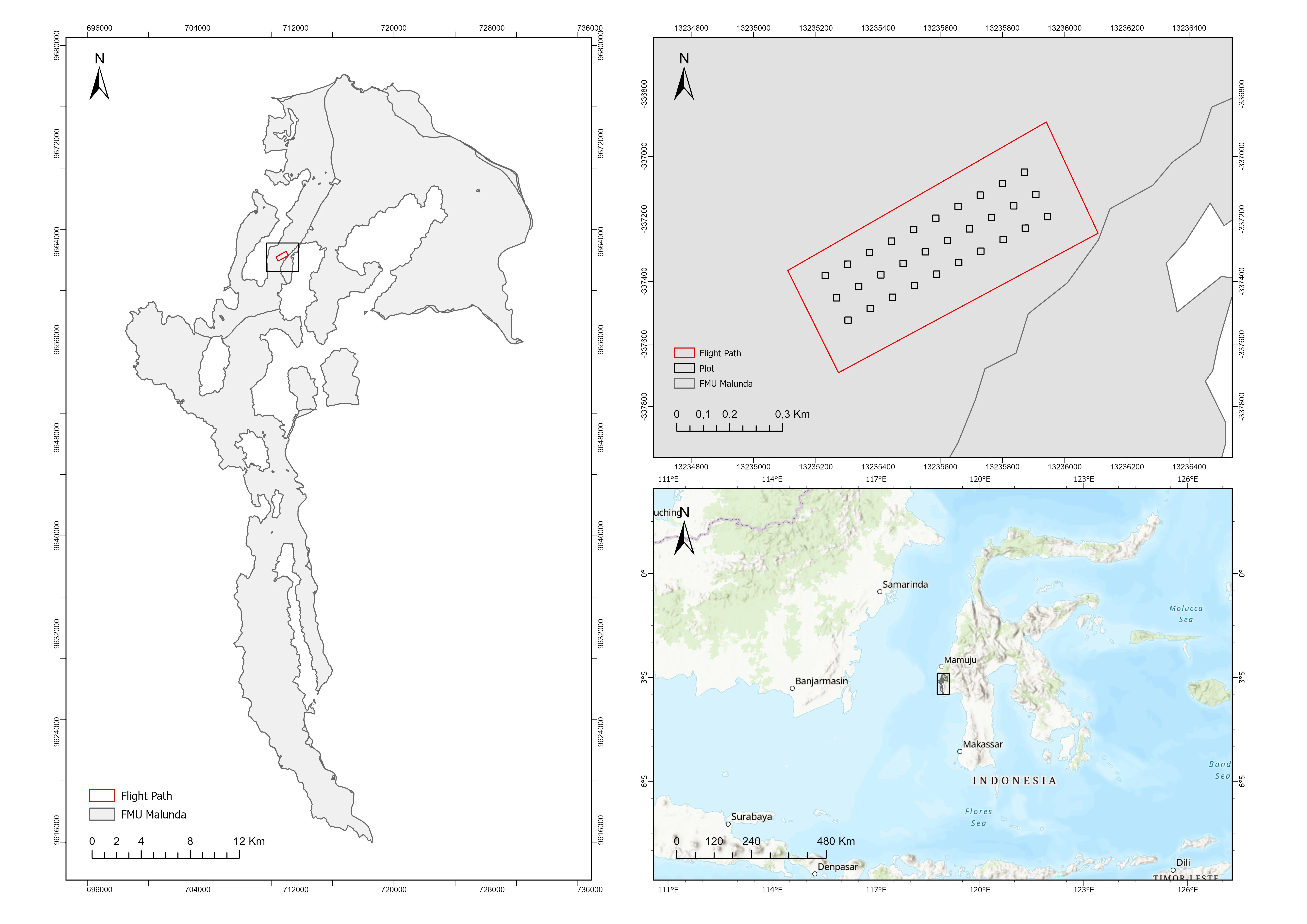

Field measurements were carried out in natural forest areas located within the Malunda Forest Management Unit (FMU) in West Sulawesi Province, Indonesia (see Figure 1). The Malunda FMU encompasses approximately 52,422.81 hectares, comprising a mix of protected forest, production forest, and limited production forest zones. All data processing and analysis were conducted at the Geospatial Information System Laboratory, Integrated Laboratory, Universitas of West Sulawesi.

Figure 1. Map of the Research Location

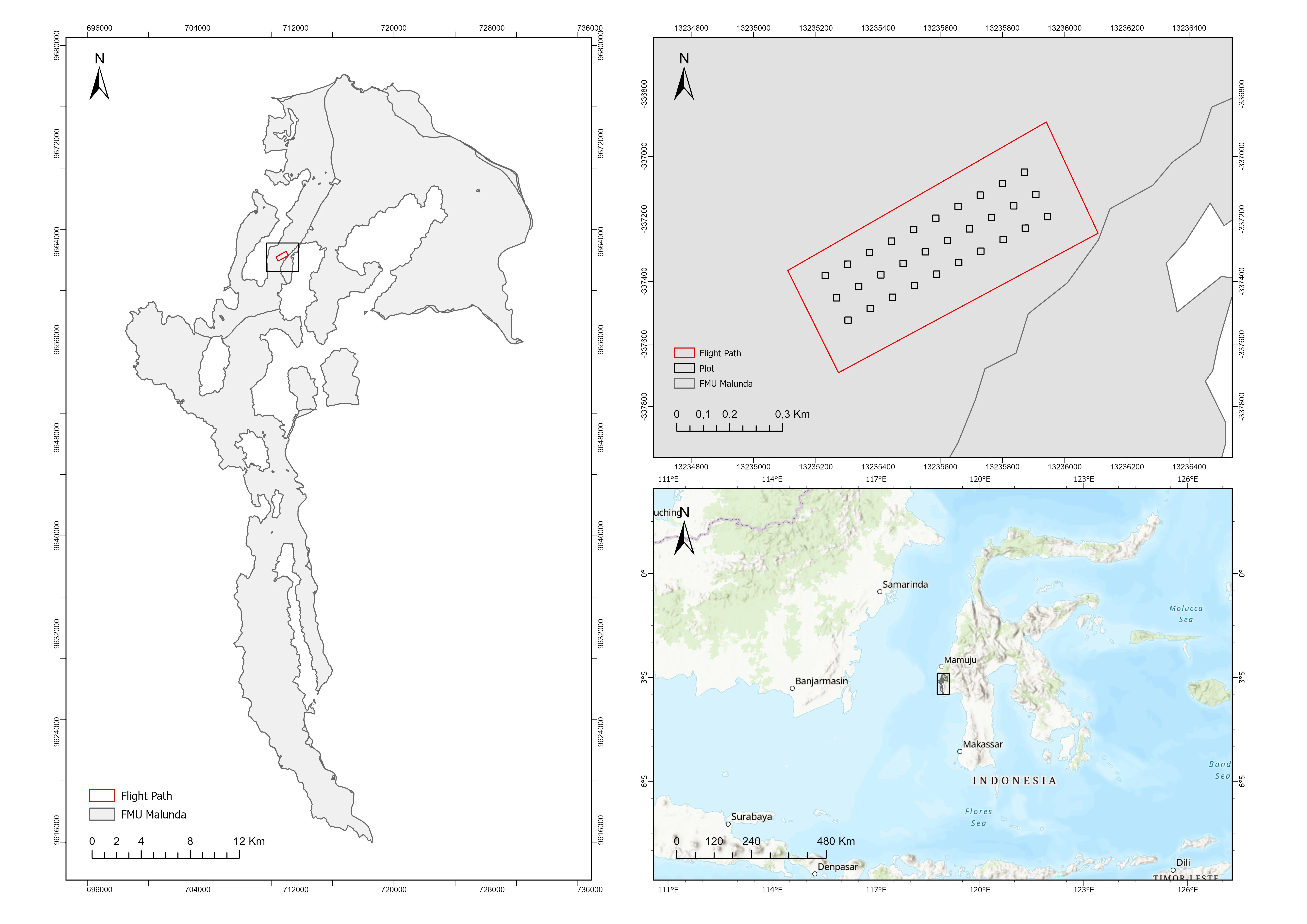

The data used in this study consisted of tree reference data including tree count, coordinates, height, and crown diameter as well as UAV-derived RGB imagery (see Figure 2). Measurement plots were set up inside the UAV flight region to get tree dimension data. Thirty square plots, each 20 × 20 meters in size, were used. The trees that were chosen for the plots had to have a minimum stem diameter at breast height (DBH) of more than 10 cm. With horizontal and vertical accuracy standards of 0.5 and 1.0 meters, respectively, a Trimble R780-2 GNSS receiver was used to record tree coordinates. Hagameter was used to conduct tree height. 614 individual trees' worth of data were successfully gathered in total (see Table 1).

Figure 2. The illustration of tree height and crown diameter measurement

Table 1. Field-measured tree dimension data

UAV-based RGB imagery was acquired using a DJI Mavic 3 Enterprise drone, equipped with a D-RTK 2 Mobile Station for enhanced positioning accuracy. A total of 190 high-resolution RGB images were successfully captured during the flight missions. The UAV image acquisition parameters are summarized in Table 2.

Agisoft Metashape Professional version 2.1.0 software was used to create point cloud data from RGB images obtained by UAVs. Because of variations in vegetation structure and image overlap, the resulting point cloud densities differed amongst the field measurement plots. Table 3 displays the specific point cloud density values for every plot.

Table 2. Parameters of UAV-RGB images

Table 3. Point cloud density and maximum height after normalization

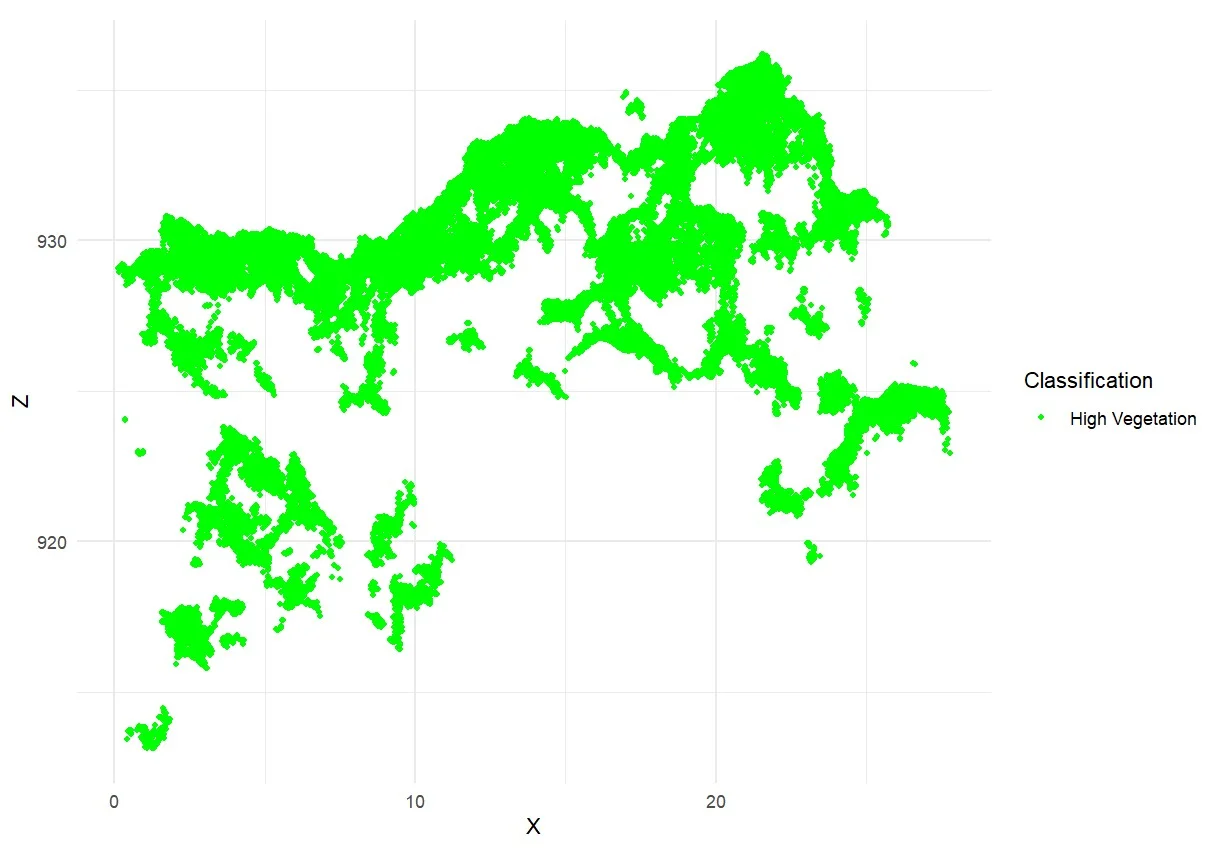

Figure 3. Point cloud after normalization: a) distribution of plots; b) vertical view of plot

The individual tree segmentation in this study was conducted using the relative tree distance algorithm developed by Li et al. (2012). This algorithm was selected due to its demonstrated effectiveness in delineating overlapping tree crowns, thereby making it well suited for application in natural forests characterized by complex and heterogeneous crown structures. This point cloud–based algorithm segments tree crown areas by analyzing the relative distance and height of points within a normalized point cloud (Li et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2023). Point-cloud normalization is performed by subtracting the interpolated ground-point elevations derived using the K-Nearest Neighbors Inverse Distance Weighting (KNNIDW) method from the original point-cloud heights, thereby producing a dataset in which the ground surface is standardized to an elevation of zero. The segmentation technique iteratively divides crown borders according to vertical and horizontal proximity after first finding local maxima, which are thought to represent treetops (Marcello et al., 2024). The lidar package was developed by Roussel et al. (2020), which offers specific features for managing and separating individual trees from point cloud data (Hardenbol et al., 2021), was used for all processing in R. Figure 4 shows the process for segmenting specific trees.

The Li et al. (2012) function has several arguments in individual tree segmentation, including threshold numbers for tree space (dt1 and dt2), height of tree dominant (Zu), if point elevation is greater than Zu, dt2 is used, search radius (R), minimum height of tree (hmin), and maximum radius of crown (speed_up) (Roussel et al., 2020). In executing this function, we adjusted the tree parameters for each plot with these arguments, where dt1 = minimum tree space, dt2 = mean tree space, R = mean radius of crown, Zu = mean tree height, hmin = minimum tree height, speed_up = maximum radius of crown.

Figure 4. Flow Chart of Data Processing

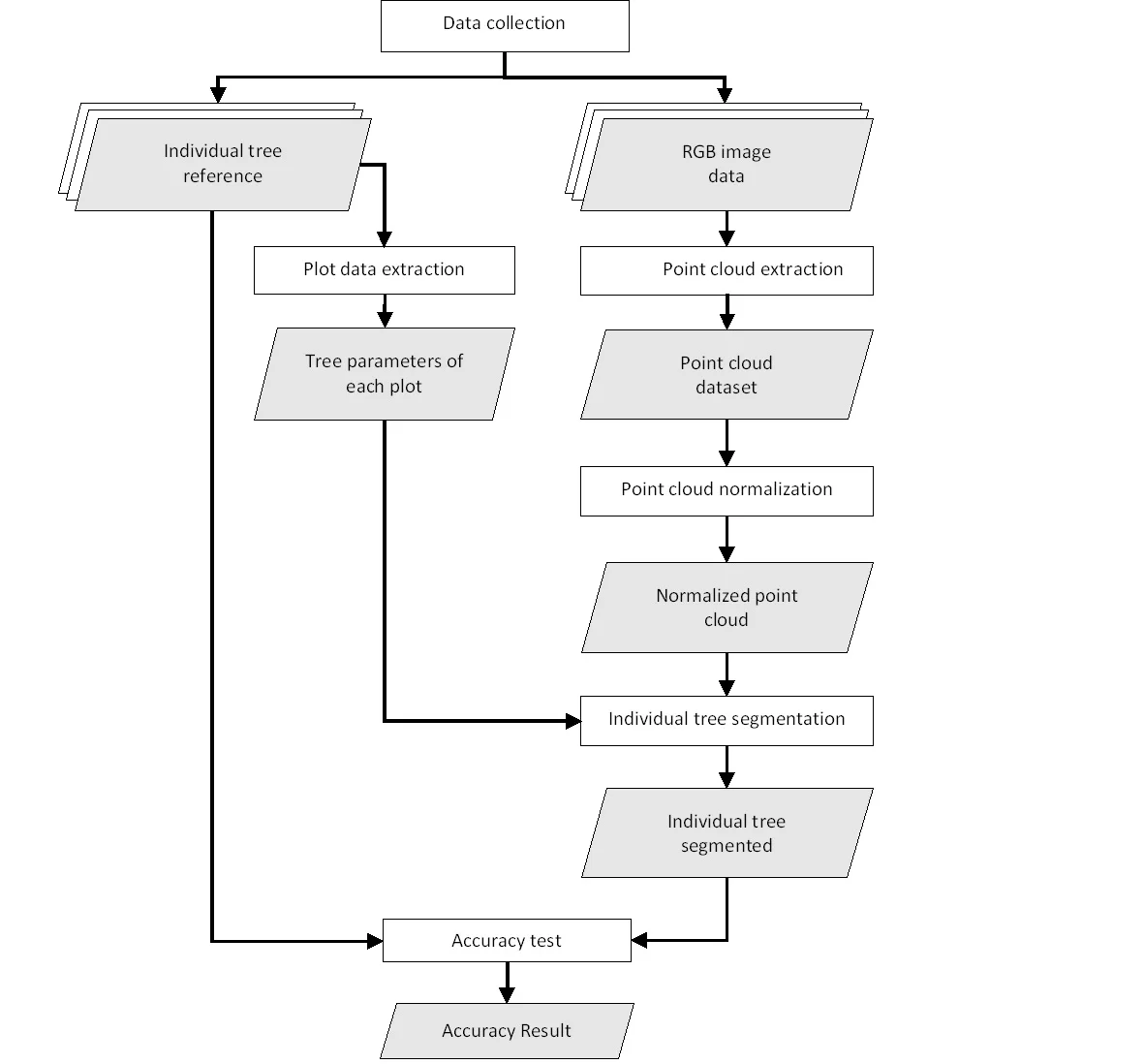

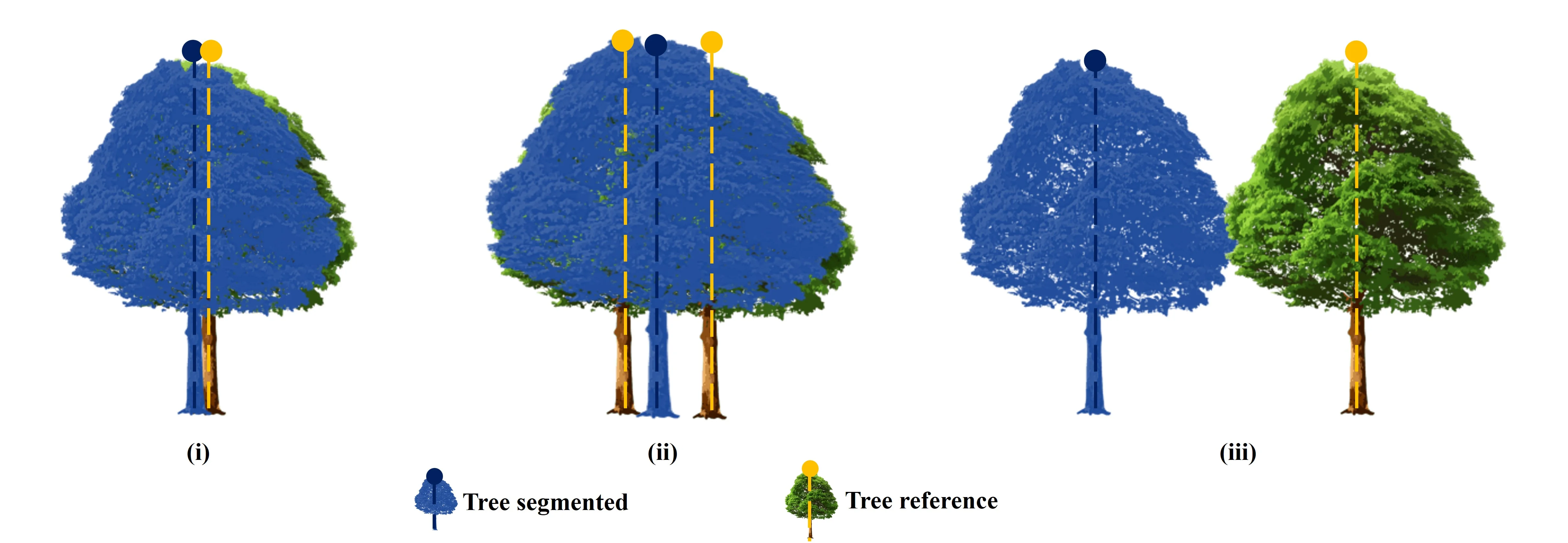

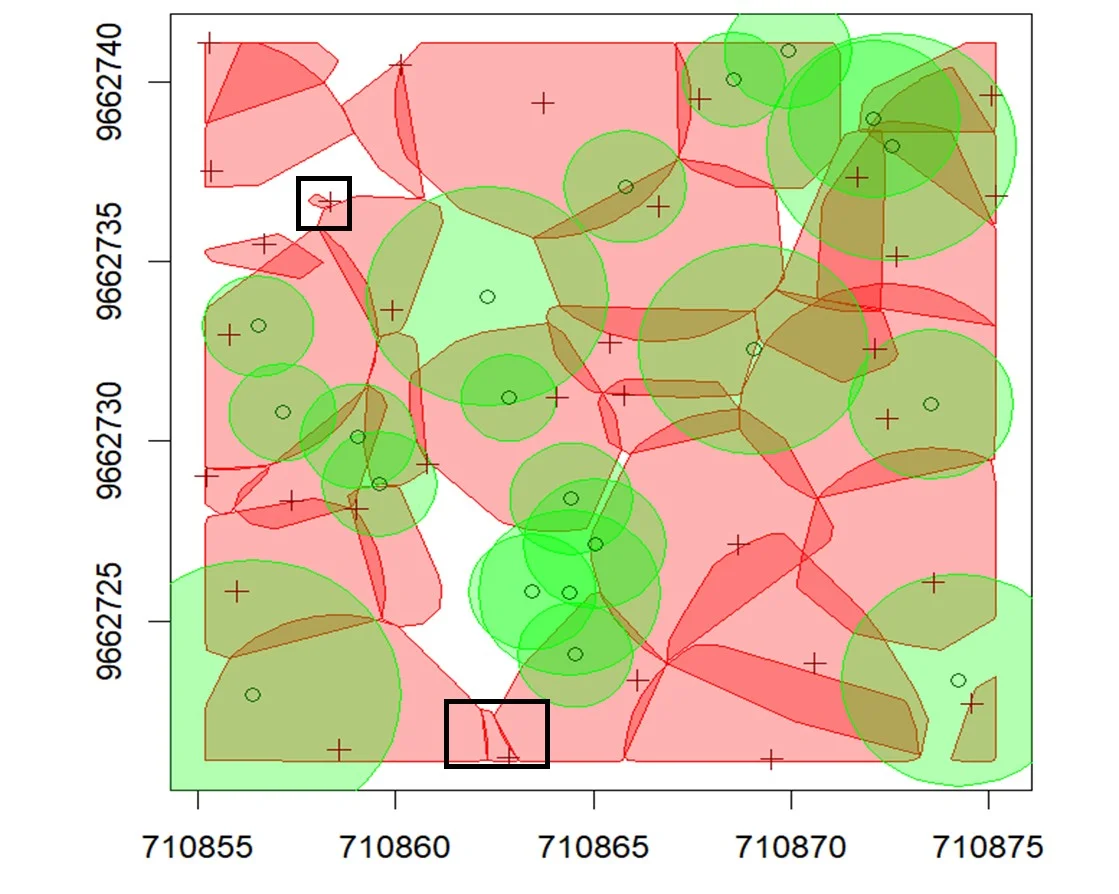

The accuracy of individual tree segmentation was evaluated by comparing UAV-RGB-derived tree data with field-measured reference trees. The assessment followed criteria outlined by Wallace et al. (2014), which define a match between segmented and reference trees based on three conditions: (i) the distance between a UAV-RGB-derived tree and a field tree must be less than 60% of the average tree spacing within the plot; (ii) the canopy of the UAV-RGB tree must overlap with the canopy of the field tree by at least 20%, calculated from the area of the intersection divided by the area of the field canopy; and (iii) if multiple canopies overlap with a single field tree, the closest match is determined using the 2D Euclidean distance.

Based on these matching criteria, segmentation accuracy was classified into three categories, as adapted from Irlan et al. (2020): (i) True Positive (TP) a tree correctly segmented in accordance with all matching rules; (ii) False Negative (FN) a field tree not correctly segmented or merged with neighboring trees; and (iii) False Positive (FP) a segmented tree that does not correspond to any actual field tree. A visual representation of this evaluation process is provided in Figure 5.

The recall (r), precision (p), and F-score values are computed to assess the accuracy of individual tree segmentation (Li et al., 2012; Mohan et al., 2021). Precision evaluates the accuracy of tree segmentation across all detected trees, recall shows the percentage of true trees that are correctly segmented, and F-score calculates the overall accuracy by taking into account the r and p values of the segmented trees using the following formula (Ahmadi et al., 2022; Gan et al., 2023; Marcello et al., 2024; Yu et al., 2022):

Precision = TP / (TP + FP) (1)

Recall = TP / (TP + FN) (2)

F1-score = 2 × (Precision × Recall) / (Precision + Recall) (3)

Figure 5. Three Type of segmentation: (i) TP; (ii) FN; (iii) FP

The accuracy test of tree coordinates and crown radius used is the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) (Irlan et al., 2020). This accuracy test is only carried out on trees that are correctly detected (TP). The equation used to calculate RMSE is as follows (Ahmadi et al., 2022; Gan et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2023):

RMSE = √(Σ(ỳi - yi)² / n) (4)

Where, ỳi is the coordinate and crown radius of the tree predicted, and yi is the coordinate and crown radius of the tree reference. n is the number of trees.

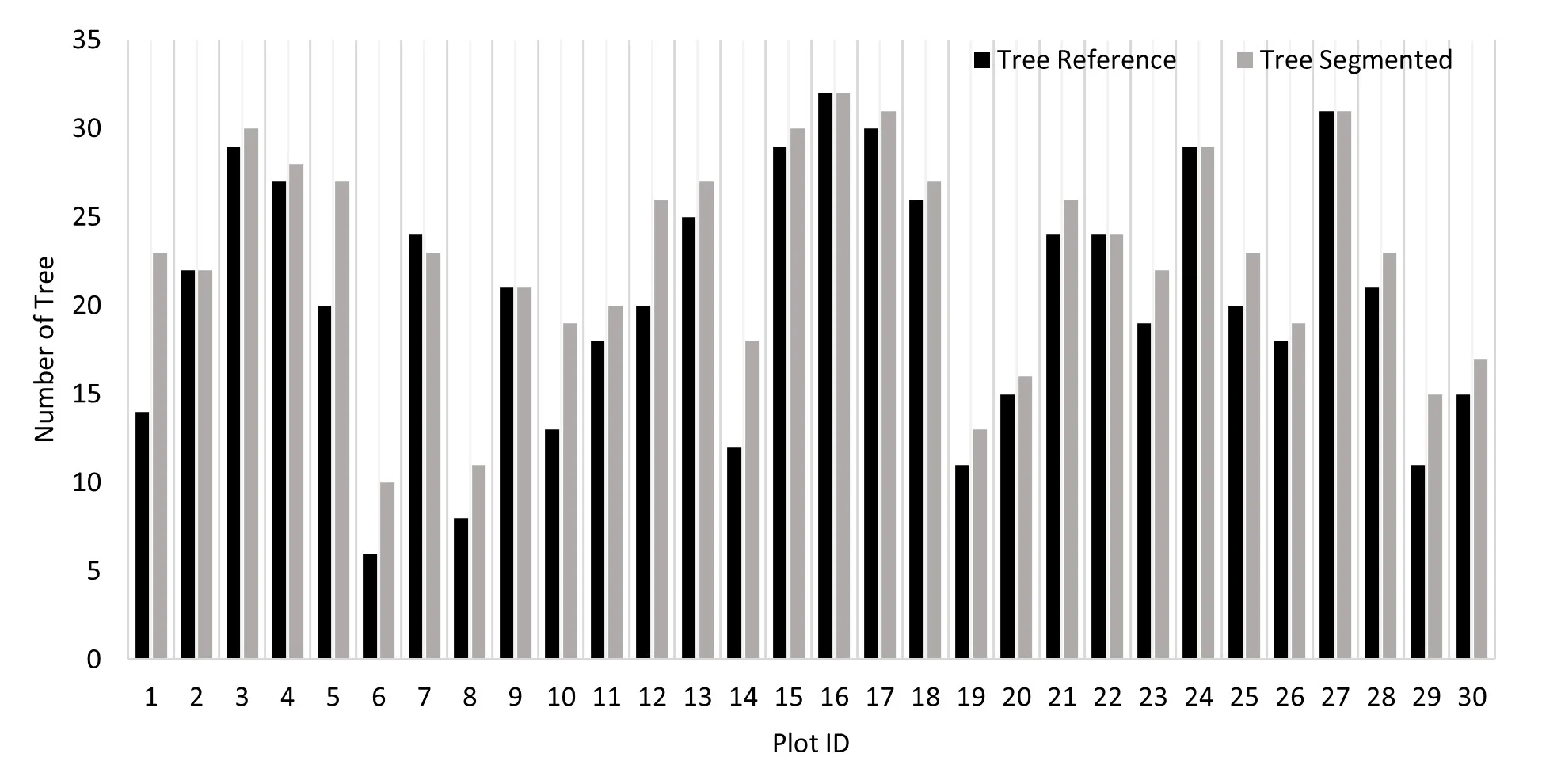

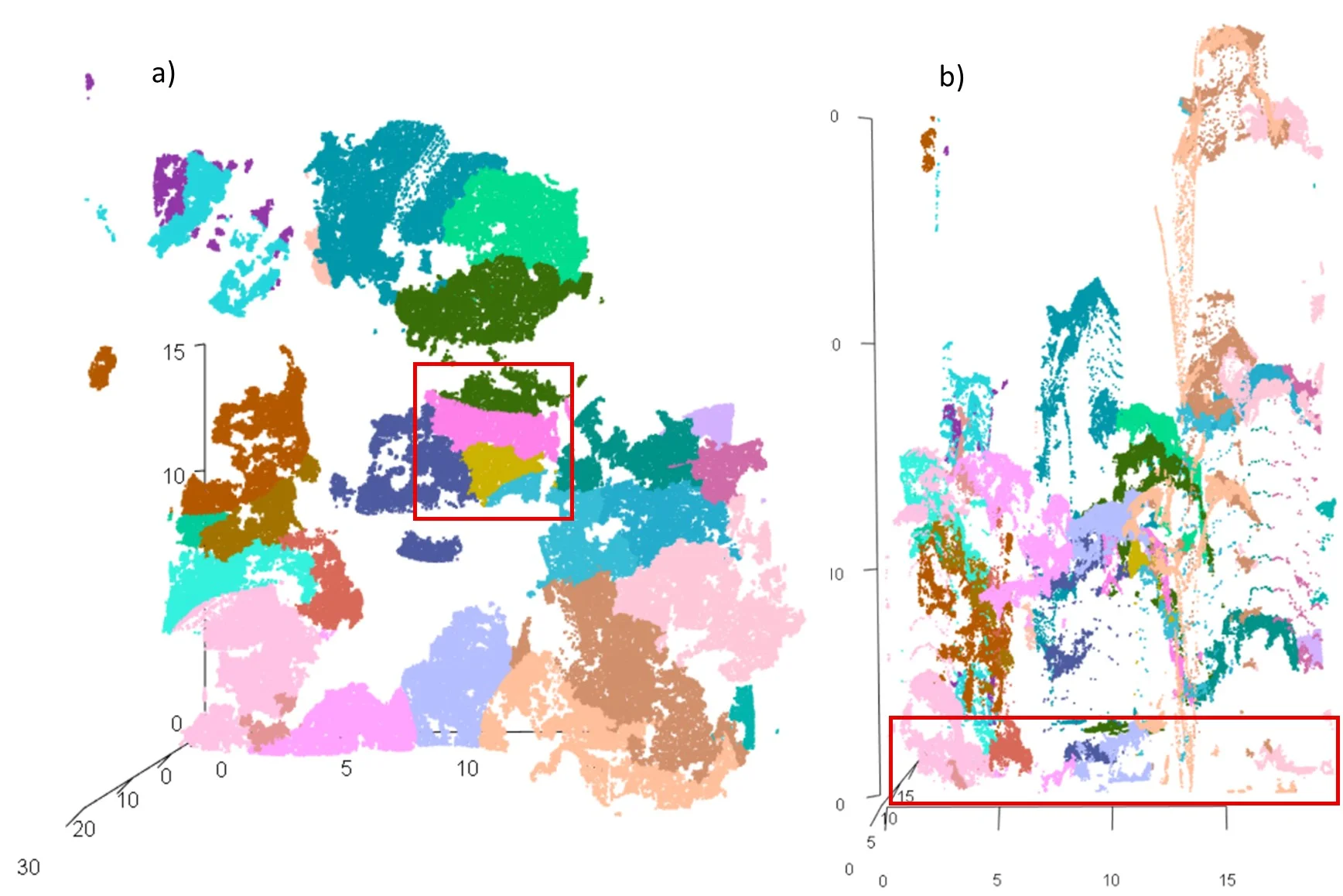

Figure 6 shows the outcomes of segmenting individual trees using point clouds created from RGB photos. The point cloud-based algorithm successfully segmented 683 trees in total. The segmentation results show a propensity to overestimate the number of trees. Small canopy gaps or understory elements may have been mistakenly classified as individual trees in plots with relatively low tree densities, such as Plot IDs 1, 6, and 8, where this overestimation was especially noticeable.

Figure 6. Number of tree reference and tree segmented each plot

The relationship between the number of reference (field-measured) trees and the number of segmented trees per plot is illustrated in Figure 7. A relatively strong positive correlation was observed between the two, with a correlation coefficient of r = 0,94 and determination coefficient of R2 = 0.89. While the total number of field-measured trees across all plots was 614, the point cloud–based segmentation algorithm identified 683 trees. This disparity implies that the approach has a tendency for over-segmentation, in which individual trees are inadvertently split up into several segments. Fascinatingly, this result is in contrast to Li et al. (2012)'s findings, which showed that the same algorithm tended to yield under-segmentation, especially in dense forest stands. The structural features of tropical natural forests or variations in UAV data resolution and point cloud density could be the cause of the over-segmentation seen in this study. Identifying and delineating tree crowns with precision in dense tropical forests is a difficult task (Aubry-Kientz et al., 2021).

The accuracy assessment of the individual tree segmentation method using UAV-RGB-derived point clouds demonstrated moderately strong performance (see Table 4). Out of the total number of field trees, 384 were correctly segmented (True Positives, TP). In contrast, 178 trees were missed or merged with neighboring trees (False Negatives, FN), and 121 trees were incorrectly identified as trees where none existed (False Positives, FP). The overall accuracy metrics yielded a recall (r) of 0.68, a precision (p) of 0.76, and an F-score (F) of 0.72, indicating a balanced trade-off between omission and commission errors.

Segmentation accuracy varied significantly at the plot level. F-scores ranged from 0.18 to 0.82, recall values from 0.20 to 0.86, and precision values from 0.17 to 1.00. This fluctuation most likely results from variations in point cloud quality, tree density, and local forest structure between plots.

Tree position accuracy was evaluated using the 384 correctly segmented trees (True Positives). The results of this assessment are presented in Table 5. The overall Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for tree position was 1.95 meters, with an average distance between the predicted and reference tree locations of 3.37 meters. At the plot level, tree position accuracy varied, with RMSE values ranging from 0.77 to 2.84 meters.

It is crucial to remember that several circumstances could have caused positional errors. First, a baseline degree of uncertainty is introduced by the horizontal precision of the reference tree coordinates, which are determined using a GNSS receiver with a threshold of 0.5 meters (Pang et al., 2021). Second, while the segmentation method determines tree positions based on the highest point in the point cloud, which usually corresponds to the top of the crown, reference tree coordinates were taken at the base of the tree trunk (Aubry-Kientz et al., 2021; Deng et al., 2024). Systematic positional inconsistencies were probably caused by this methodological variation in identifying tree position crown apex versus trunk base (Li et al., 2012).

Table 6 displays the findings of the accuracy evaluation of the tree crown radius. The calculated crown radius has an overall Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 1.59 meters. Plots differed in precision; nevertheless, RMSE values varied from 0.85 to 2.77 meters. This variation could be explained by the segmentation algorithm's propensity to draw crown borders closer to the lower parts of the canopy, which might not fully capture the spread of the crown. In point cloud-based segmentation, this kind of underestimate is typical when point density is low or when overlapping canopy layers mask, the actual horizontal extent of individual crowns (Ma et al., 2021).

Table 6. RMSE of the tree crown radius in each plot

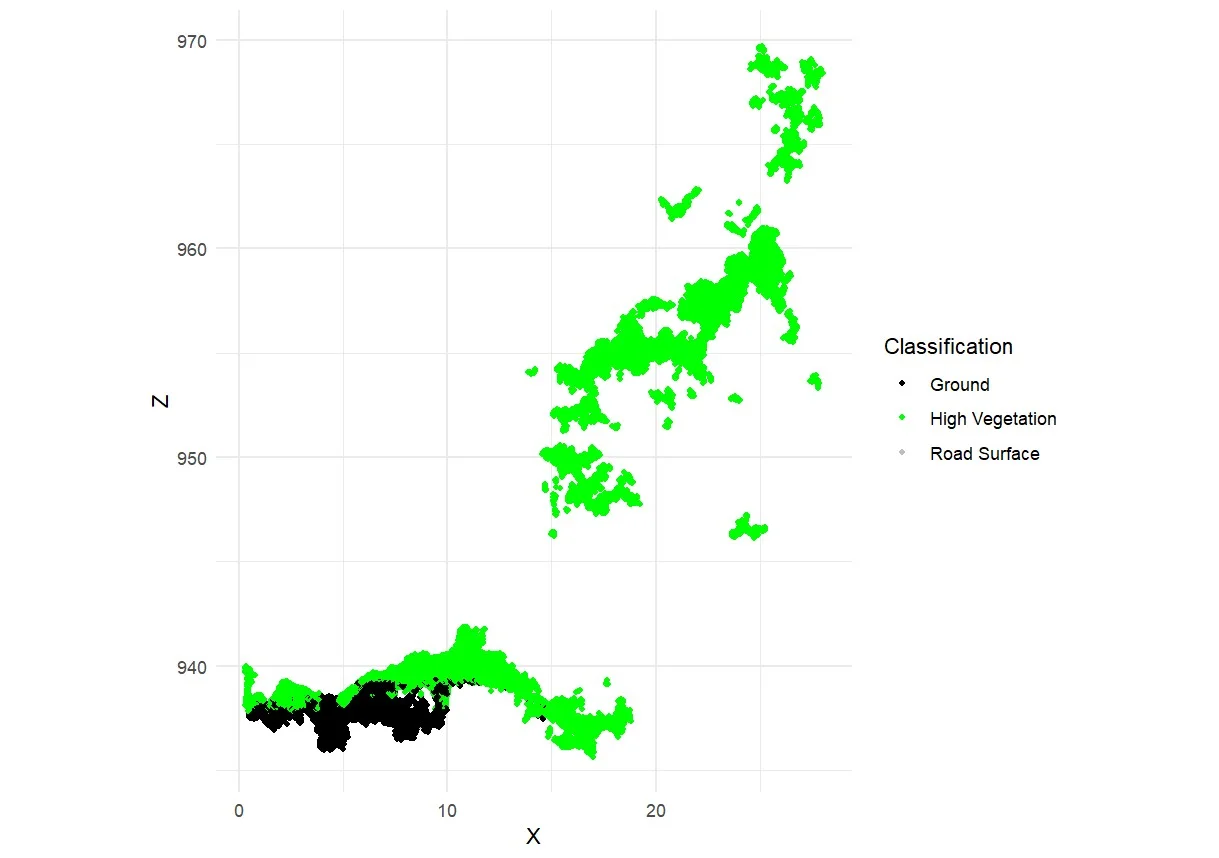

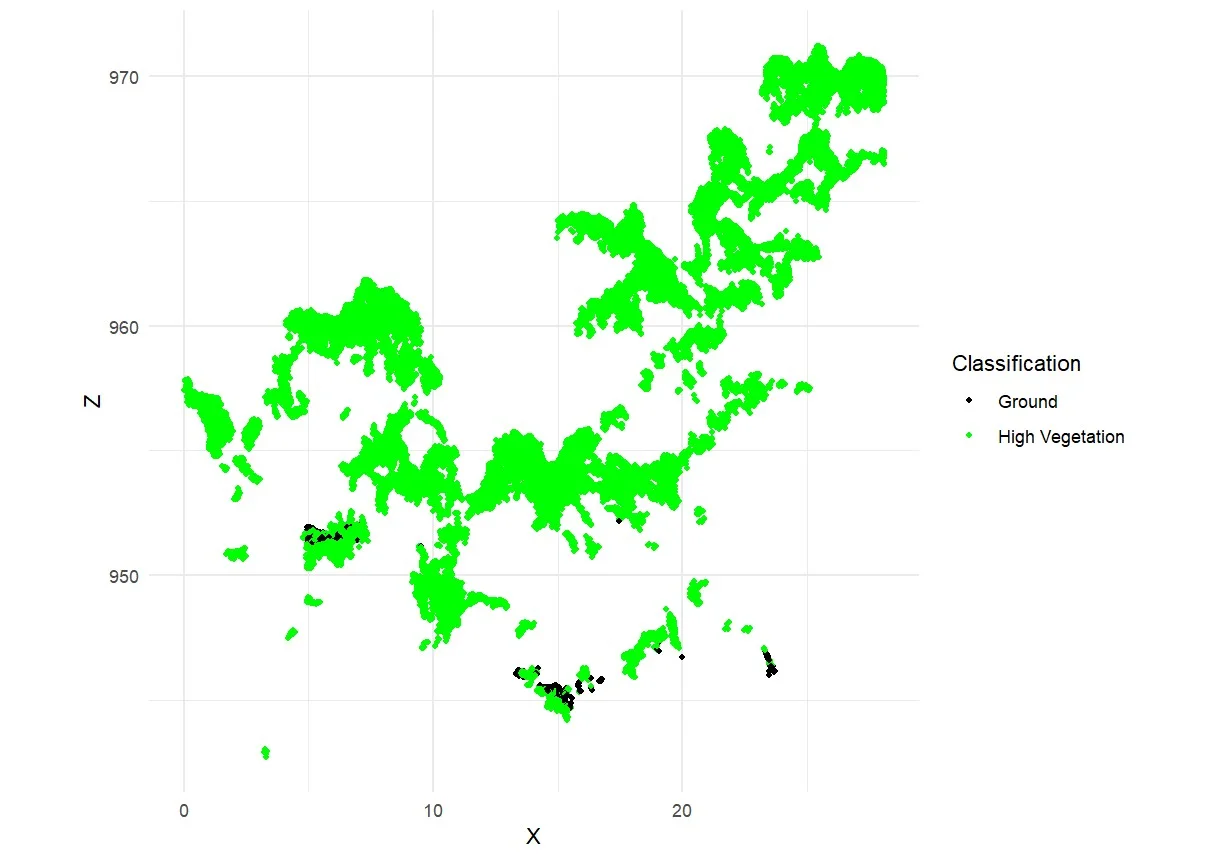

Each point in the generated point cloud corresponds to a pixel derived from RGB images. These point clouds were automatically classified into several surface categories, including soil, low vegetation, high vegetation, and road surface (Pacheco-Prado et al., 2025). However, a key limitation of RGB sensors is their inability to penetrate dense canopies, resulting in insufficient point data beneath the upper canopy layer (González-Jaramillo et al., 2019; Hanapi et al., 2019; You et al., 2023). This limitation is particularly critical for point cloud normalization, which relies on accurately identifying ground points to calculate tree height and perform segmentation. According to Dell et al. (2019), the accuracy of individual tree segmentation findings can be significantly impacted by the absence of trustworthy ground points. It is possible to classify ground points efficiently in comparatively open spaces. On the other hand, ground point categorization becomes more challenging or even impossible in plots with dense or closed canopies. This is evident in Figures 8a–8c, where ground points are visible only in sparsely vegetated areas, while Figure 8d shows no ground classification at all due to complete canopy closure. What can be done to overcome the limitations of ground points in high-density forests is to combine them with point clouds obtained from above the canopy and terrestrial point clouds (Xia et al., 2023).

Figure 8. Classification of point cloud in: a) low density; b) moderate density; c) high density; and d) very high density

One of the critical components in point cloud–based tree segmentation is the process of point cloud normalization. Normalized point clouds serve as the primary input for individual tree segmentation algorithms, as they provide accurate height information relative to the ground surface (Marcello et al., 2024). The purpose of normalization is to remove terrain elevation variability, allowing for the extraction of tree heights above ground level rather than above sea level or uneven topography (Dell et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2024).

In environments with extremely changeable or rough terrain, like the research study region, this procedure is crucial as a mention Ma et al. (2023). Errors in tree detection and crown delineation might result from segmentation algorithms misinterpreting elevation changes in the terrain as tree height if correct normalization is not used. Consequently, successful point cloud normalization and, eventually, high-accuracy individual tree segmentation depend on precise and trustworthy ground point categorization. Point cloud normalization was conducted individually for each of the 30 observation plots. To create normalized point clouds, this study used the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) interpolation technique in conjunction with Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW). A three-tier classification system was used to visually and qualitatively evaluate the normalizing output: "Yes" denotes a successful normalization, "Maybe" denotes an ambiguous outcome, and "No" denotes an unsuccessful normalization. According to the assessment results, eight plots failed to normalize correctly, four plots produced results that were unclear, and eighteen plots were successfully normalized.

As discussed in the previous section, the availability of reliable ground points is a key determinant of successful point cloud normalization (Dell et al., 2019). In many of the failed or uncertain plots, incomplete or missing ground returns caused by dense canopy cover were the primary limiting factor. Moreover, the absence of high-resolution Digital Terrain Model (DTM) data for the study area posed an additional constraint, preventing the use of alternative or more robust normalization techniques.

Given these limitations, we recommend further research focused on evaluating the performance of RGB-derived point cloud normalization methods, particularly in structurally complex tropical forest environments. Such studies are essential to understand better the constraints and potential improvements in normalization accuracy under varying forest conditions.

The results of the individual tree segmentation indicate that the applied algorithm tends to over-segmentation, leading to an overestimation of tree counts. This issue is particularly evident in trees with large, irregularly shaped crowns, which are often misinterpreted by the algorithm as multiple smaller trees (Figure 9a). As a result, a single tree may be incorrectly segmented into multiple crown regions.

Additionally, point cloud height is not considered as a limitation during the crown delineation procedure in the current segmentation approach. As a result, low-lying shrubs or understory plants might be mistakenly categorized as belonging to the top canopy, which would further increase segmentation mistakes (Figure 9b). The algorithm's absence of a minimum crown height criterion, which would have assisted in differentiating between actual tree crowns and lower vegetative layers, is the leading cause of this (Roussel et al., 2020). Future enhancements may strengthen segmentation results and reduce the misclassification of undergrowth as tree crowns by utilizing vertical filtering criteria, such as minimum crown height or canopy height thresholds.

Figure 9. a) Horizontal structure, illustrated the over-segmentation of trees (red boxes); b) vertical structure, demonstrated the understory plants (<3 m) segmented as tree crowns

Tree height thresholds, relative tree spacing, and crown width estimates are among the parameter variables that have a significant impact on point cloud-based individual tree segmentation techniques. The best way to set these settings can differ significantly depending on the type of forest, the density of trees, and the quality of the point cloud (Marcello et al., 2024). Tree counts may be systematically overestimated or underestimated because of improper or non-contextual parameter settings.

In complex and structurally heterogeneous forests, segmentation algorithms often struggle to distinguish trees from dense undergrowth or may misclassify non-tree objects as individual trees, thereby reducing segmentation accuracy, as mentioned by Ma et al. (2022) and Marcello et al. (2024). In this study, the algorithm frequently segmented trees with small crown sizes, contributing to over-segmentation in some plots (see Figure 10). It is important to note that the segmentation process in this study was based on a maximum crown width parameter, without applying a minimum crown width threshold (Roussel et al., 2020). As a result, smaller vegetation or understory elements that met the maximum width criterion may have been incorrectly classified as tree crowns. Future algorithm improvements should include a minimum crown width parameter to enhance segmentation accuracy, particularly in tropical natural forests with intricate vertical structures. This would improve crown delineation and assist in eliminating non-tree vegetation, particularly in regions with highly stratified canopy layers.

Figure 10. The segmentation results for individual trees with a small crown (black boxes)

Individual tree segmentation utilizing RGB images-derived point cloud data is significantly hampered by high crown density and overlapping canopy layers. The variety of tree species seen in tropical natural forests, each having unique branching patterns and crown morphologies, adds to the complexity. Furthermore, successful segmentation in dense, multi-layered forest environments is more challenging due to RGB point clouds' intrinsic limitations in collecting complex three-dimensional structures beneath the canopy.

Despite these challenges, the findings of this study demonstrate that RGB point cloud–based segmentation remains a feasible and cost-effective approach for individual tree detection in tropical forest conditions. To further enhance the performance and applicability of this method, future work will focus on the following directions: 1) Improving the quality of UAV-RGB point clouds by integrating them with terrestrial point cloud data to capture vertical canopy structures better. 2) Developing segmentation algorithms tailored to tropical forest environments by incorporating additional parameters, such as minimum crown width, to reduce misclassification of understory vegetation. 3) Estimating aboveground biomass at the individual tree level using UAV-RGB point clouds. 4) Integrating UAV point cloud data with satellite imagery to support large-scale biomass estimation across diverse tropical forest landscapes. These efforts aim to improve the precision and scalability of remote sensing techniques for forest inventory, carbon accounting, and sustainable forest management in complex tropical ecosystems.

This study evaluated the accuracy of point cloud–based individual tree segmentation derived from RGB images in tropical natural forests of Indonesia. A total of 683 trees were successfully segmented, comprising 384 True Positives (TP), 178 False Negatives (FN), and 121 False Positives (FP). The segmentation results revealed a tendency toward over-segmentation, particularly in areas with lower tree density or complex crown structures. The primary limiting factor was incomplete or missing ground measurements due to dense canopy cover.

With a recall (r) of 0.68, precision (p) of 0.76, and F-score (F) of 0.72, the overall accuracy of individual tree segmentation demonstrated a moderately strong performance. Additionally, evaluations of spatial accuracy were carried out for the trees that were appropriately segmented. Tree location had an RMSE of 1.95 meters, while crown radius had an RMSE of 1.59 meters. Given its affordability in comparison to LiDAR-based techniques, these results imply that UAV-RGB point cloud–based segmentation is a practical and effective method for identifying individual trees in tropical natural forests. Addressing the problems of understory misclassification and over-segmentation, however, still needs work. Future research will concentrate on the following areas: 1) improving RGB point cloud quality, possibly by integrating terrestrial point cloud data; 2) creating better segmentation algorithms with parameters like minimum crown width; and 3) expanding applications to include biomass estimation and large-scale forest monitoring by fusing satellite remote sensing data with UAV point clouds.

The First author (I) collected data, processed data, wrote and edited the draft of the manuscript. UKA, as the second author, assisted in processing the data, wrote, and edited the manuscript. SHO assisted in collecting the data and advised on the research methodology. MLI assisted in collecting and processing data. ASJ assisted in collecting and processing data. TBA assisted in giving advice on research methodology, and the last author, CA in the gave advice on research methodology and analysis data.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This research was carried out through the Bima Program through the 2025 and The authors would like to thank theMinistry of Higher Education, Science and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia for funding and supporting this research.

Zhou, X., Wang, H., Chen, C., Nagy, G., Jancso, T., & Huang, H. (2023). Detection of Growth Change of Young Forest Based on UAV RGB Images at Single-Tree Level. Forests, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/f14010141